Tamiya Iemon is the absolute worst. I have seen multiple adaptations of Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan, from Keisuke Kinoshita’s Shinshaku Yotsuya Kaidan / Yotsuya Kaidan Part 1 & Part II (1949) to Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1959 adaptation, Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan / The Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959) to Takashi Miike’s Over Your Dead Body (2014) and even more that I won’t get into here. In each, Iemon remains just as appalling as the first time I saw him. I believe if I saw the adaptations from 1911, 1912, 1925 or even 1937, Tamiya Iemon would still be the absolute worst. It seems like a violation of some law of fictional dynamics or emotional conservation that this should be so, but it nevertheless is. Just in the course of writing this, I have learned a new terrible thing about Iemon every day. Did you know that Iemon not only killed his first wife’s dad, but kicked his second wife’s mom into a canal and left her to drown? Well, now you do. Iemon has been hateful, appalling and absolutely the worst since 1825.

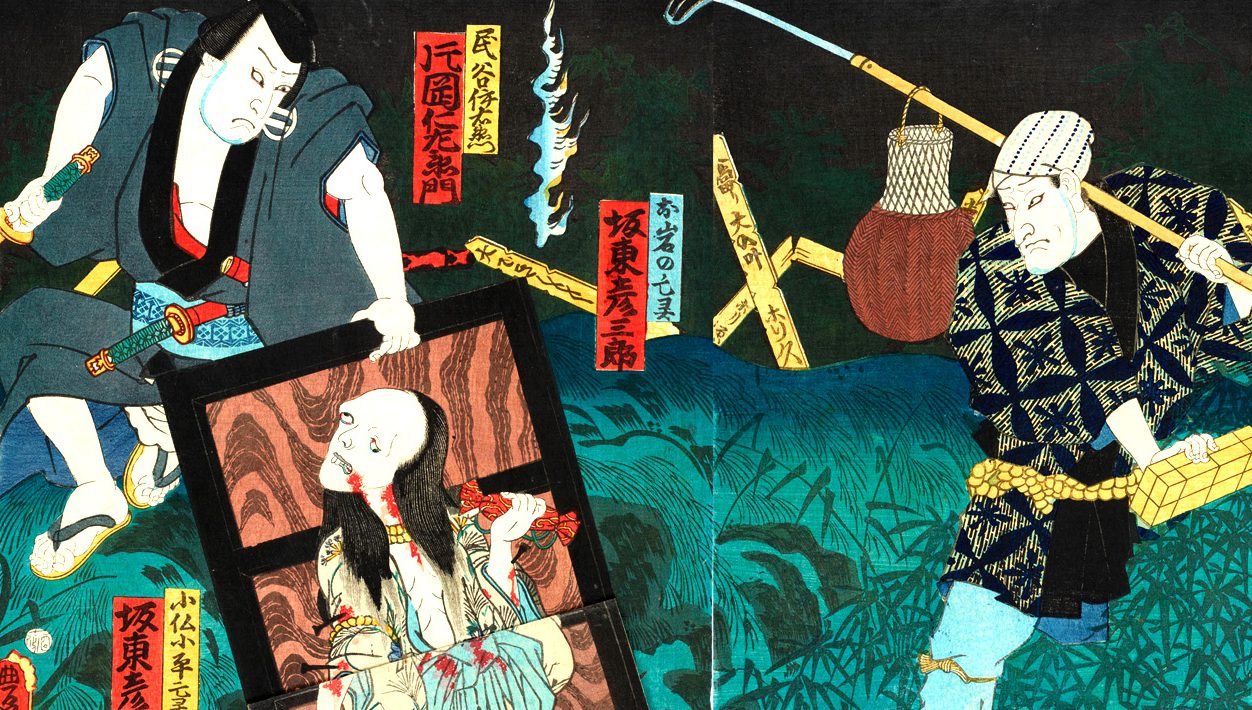

Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan is a story originally written for the Kabuki stage and has been adapted many times. Written by Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1755-1839), Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan was first staged in Edo’s Nakamura-za Theater in 1825. If the name Tsuruya Nanboku IV sounds familiar and you’re not just confusing him with the master playwrights, Tsuruya Nanboku I-III, you might remember him for his relation to Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko. Tsururya Nanboku IV wrote a play about a ghost cat, called, Okazaki Ghost Cat / Traveling Alone To The 53 Stations (1827) which influenced subsequent cat stories. Tsuruya wrote many, many plays for one of Edo’s most prestigious theaters. And he was an innovator in kabuki, creating kizewamono, a genre of real life, down and dirty drama focused on outsiders and outcasts that is still reflected in Japanese film. Love a sassy middle-aged woman who’s not afraid to throw down or who runs a yakuza outfit without taking any of your lip in an episode of Zatoichi or Kurosawa film? That’s Tsuruya’s akuba. Stunned at how that beautiful man can be such a sociopathic bastard, that’s on Tsuruya, too, and his invention of the iroaku, the handsome scoundrel. And with plays like Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan, he pioneered the ghost play — the kaidanmono — in a more realistic and mundane setting—a world of ronin, prostitutes, poor samurai, and masseurs who run gambling dens.

Horror has a more central role in Japanese theater than it does in respectable English language theater. We tend to overlook the fact that Hamlet is a ghost story or a story about possibly being manipulated into murder by infernal forces. Beowulf is pretty much a slasher in which the descendant of an ancient murderer is fed up with the kids partying over at Hrothgar’s mead hall. (In Beowulf II: Grendel’s Redemption, Grendel’s mom takes revenge for her murdered son by killing all the Geats at Camp Murky Mere). But the Japanese theatrical tradition itself began with straight up spirit possession of priestesses. And Kabuki was invented by a woman, Okuni, and, at first, exclusively performed by women, until the Shogun’s officials decided that it really pissed them off when women made fun of them. Also, too sexy. (And then young male actors and their forelocks were too sexy. Authoritarianism worries a lot about too sexy).

Ghost stories wend their way from Noh, Kabuki and the Bunraku puppet theater all the way through “J Horror” and the vengeful ghost ladies with invasive hair of today. There are many tales of love, bitterness and vengeful ghosts, but like a certain Scottish play, Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan is unique in having a curse associated with it. Oiwa is one of the pre-eminent ghost ladies, and her story was so powerful that her character became, in some sense, real. In his play, Tsuruya integrated a 17th Century account of a woman named Oiwa who died and came back as a ghost to punish her unfaithful husband. And in at least one production, the audience was told that between acts Oiwa was watching them and could even be seated beside or behind them to spooky effect. Productions of Yotsuya Kaidan have been troubled with accidents and injuries and traditionally casts, particularly the actor playing Oiwa, make offerings at Oiwa’s grave at Myogyo-ji to propitiate her and protect any production.

Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan premiered over two nights with a performance of Kanadehon Chushingūra, aka, The Forty-Seven Loyal Ronin. It was a ronin-tastic evening as, on one hand, we see the loyalty of samurai bent on avenging their murdered lord and, on the other, the cruddiness of Iemon, a masterless samurai driven to betray his wife because the temptations of wealth and position. And, I believe, general dickishness. Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan is still often performed with Kanadehon Chushingura. And Tsuruya mixed in some that story in his own, adding loyalties to one side or the other of Chushingura‘s central conflict. Kinji Fukasaku brings back some of this history in his own 1994 film, Crest Of Betrayal, in which he squishes together both Yotsuya Kaidan and Kanadehon Chushingūra into one film, called in Japanese, Chushingūra Gaiden Yotsuya Kaidan. I haven’t seen Crest of Betrayal, but I assume most of the running time is taken up with each and every one of the forty-seven loyal ronin telling Iemon that he is the worst. In fact, I assume there is a whole musical performance in which the entire cast sings about how Iemon is the absolute worst. How is he the worst? I am half-tempted to just list all the terrible things Iemon does and leave it at that.

The Tale of a Terrible Man

Iemon is one of those poor samurai who was generally screwed by hundreds of years of peace under the Tokugawa Shogunate. A couple of hundred years of military dictatorship means that there are a lot of executions, but not much in the way of war. There are only so many positions. A lot of jobs are theoretically beneath samurai. The upside, of course, is that the Edo period is a swell time for the theater, woodcuts and people writing books about bushido and different sword techniques. And things would’ve gotten a lot better for everyone involved, I think, if Iemon had taken an interest in the theater or writing manifestos. But rigid class stratification and the resulting limited opportunities are no excuse for being an awful human being, Iemon. After being fired for embezzling clan funds, Iemon has taken up making and selling umbrellas to support his wife, Oiwa, and their son. And it’s hard on Iemon. Samurai are supposed to serve a lord. They are supposed to fight and die. They are not supposed to sell umbrellas for a living.

Oiwa’s father is Yotsuya Samon, a former retainer of the late Lord Enya, who died during the events of The Forty-Seven Loyal Ronin. Enya also happens to be the lord who fired Iemon. Things are not going well for the Yotsuya family. Samon has become a beggar. Oiwa’s sister Osode is secretly working as a prostitute at a tea house to help support the family. But even with all that going on, Samon does not have time for Iemon and his terribleness. In fact, he seems to think Iemon is the most terrible thing going on. He asks Iemon to leave Oiwa. And it turns out that he’s right that Iemon is the worst thing going on with his family, because Iemon immediately murders him. Meanwhile, his friend and fellow murder enthusiast, Naosuke kills his own master thinking he’s killed Osode’s husband, Yomoshichi, and that will get him in good with her. Because who doesn’t like murder? But Yomoshichi’s all involved with the forty-seven ronin and very much alive in hiding. Iemon and Naosuke promise Oiwa and Osode that they will avenge the dead. Because Naosuke is almost the worst, he only agrees to do this if Osode will shack up with him. Osode agrees to a point, but won’t sleep with him till her father is avenged. So Naosuke peddles “Dutch medicine” on the street. Which I think is slang for “becomes a meth dealer.” Meanwhile, Iemon is finding the life of a ronin umbrella-maker tiresome. Oiwa has just given birth, but her recovery is slow. But after seeing Iemon’s rarely used sword skills and handsome scoundrel face on the street one day, Oume, the girl next door, falls in love with him. She is the grand-daughter of Itō Kihe, a samurai with a powerful and wealthy lord who was the enemy of Lord Enya.

His own love life stymied, Naosuke keeps telling Iemon how much the cutie next door likes him and how he’d be on easy street if he married her. Naosuke sets up a meeting with Oume’s family and everyone is all, “Boy, Iemon, it’d be so easy for you to marry our beautiful daughter and be on easy street the rest of your life with wealth and a cushy, respectable position with the winning side. All you have to do is kill your wife—or at least let Oume’s family disfigure her with poison, set her up to be raped by a dude who’s in love with her and then say she’s an adulterer so you can divorce her or, really, execute them as is your right as a samurai. Even as the worst samurai.”

His own love life stymied, Naosuke keeps telling Iemon how much the cutie next door likes him and how he’d be on easy street if he married her. Naosuke sets up a meeting with Oume’s family and everyone is all, “Boy, Iemon, it’d be so easy for you to marry our beautiful daughter and be on easy street the rest of your life with wealth and a cushy, respectable position with the winning side. All you have to do is kill your wife—or at least let Oume’s family disfigure her with poison, set her up to be raped by a dude who’s in love with her and then say she’s an adulterer so you can divorce her or, really, execute them as is your right as a samurai. Even as the worst samurai.”

And so Iemon does think about it, because murder is his solution to all problems—or even mildly vexing occurences. The Ito family, however, like disfigurement. They think ruining Oiwa’s good looks will give Iemon the nudge he needs to leave her and marry Oume. So they give Oiwa “medicine” and poison her in the guise of helping her. They needn’t have worried, though, because Iemon has set in motion his own more murderous plan to entrap Oiwa as an adultress entangled with their old family friend Takuetsu, who is also a masseur, yakuza and manager of both a gambling house and the brothel where Osode worked. The poison horribly disfigures Oiwa. Her left eye swells and droops. Her hair comes out in bloody clumps. Horrified, Takuetsu can’t go through with the rape. Instead, he hands Oiwa a mirror and tells her that Iemon has arranged all of this. Taking up a sword to give everyone what for, Oiwa accidentally cuts her throat and dies cursing Iemon. Iemon kills a former servant, Kohei, just because. And then Iemon has Oiwa and Kohei’s bodies nailed to opposite sides of a door and thrown in the canal. But Iemon will wish that Oiwa had killed him, because she might’ve been a frail wife, but she is a terrifyingly effective ghost.

Iemon marries Oume right after dropping his wife and betrayed friend in the river. For her part, Oiwa gets right to work haunting him. Appearing to him on his wedding night, she tricks Iemon into believing Oume is Oiwa and he kills the poor kid. He kills Mr. Ito. And he kicks Oume’s mother into the canal, because why not? After his rampage at the Itos’ house, he retreats to a monastery on Snake Mountain, hoping Oiwa (and, to a lesser extant, Kohei) can be exorcised. But it doesn’t work. Oiwa is determined and angry and she finally drives him to his death: dragging him to hell in his dreams and chasing him out of the temple to be killed by Yomoshichi. (Yomoshichi was a little peeved to discover Osode shacked up with Naosuke, but Osode kills herself, leaving a letter revealing that Naosuke was her younger brother all along. Feeling guilty and creeped out, Naosuke kills himself, too). So, all’s well that ends with Iemon dead.

From Stage to Screen

So that’s generally the play. There have been easily a kajillion stagings, film and television adaptations of the story. Lone Wolf And Cub / Babycart Assassin‘s Tomasiburo Wakayama plays Iemon in two films— with Chieko Soma as Oiwa in Masaki Mori’s 1956 Yotsuya Kaidan and with Keiko Fujishiro as Oiwa in Yasushi Kato’s 1961, The Ghost Of Oiwa. Tatsuya Nakadai plays Iemon and Mariko Okada plays Oiwa in Shiro Toyoda’s 1965 Yotsuya Kaidan / Illusion of Blood. But I’m just going to focus on Keisuke Kinoshita, Nobuo Nakagawa and Takashi Miike’s adaptations here.

Kinoshita’s portrayal of Iemon (Ken Uehara) is fairly sympathetic. Oiwa’s haunting is a manifestation of Iemon’s guilt more than anything. But while it is comparatively naturalistic, Kinoshita’s film is still plenty spooky, with some startling images. Iemon is not so much a murder machine, as a ronin whose resentments and sense of samurai entitlement are easily played upon by a sly robber and likely sociopath, Naosuke (Osamu Takizawa), whose good friend Kohei (Keiji Sada) has just gotten out of prison and makes no secret of his creepy, creepy lust for Oiwa. In Kinoshita’s adaptation, Oiwa (Kinuyo Tanaka) worked in a teahouse and Iemon met her there. They fell in love and married while Kohei was in prison. Osode (also played by the amazing Kinuyo Tanaka) and Yomoshichi have a normal, no murder or poison marriage. Osode doesn’t like how Iemon treats Oiwa and tells Oiwa that. She even gives the poor kid one of her fancier new kimonos hoping that will cheer Oiwa up after a recent miscarriage. Iemon runs hot and cold with Oiwa, or maybe room temperature and cold. He takes her fishing, but he also throws her teahouse days in her face. He doesn’t specifically murder her, but he listens to Naosuke’s plot to murder her and set him up with Oume. And he goes to meet Oume’s family. Iemon comes home to find Oiwa in pain with a burned eye and takes up Naosuke’s offer of a burn cream. And, surprise, the burn cream kills Oiwa. Naosuke and Iemon kill Kohei and then it’s anchors aweigh in the canal.

Part I sets the stage of Iemon’s actions. His hatred of his poverty. His misery and shame at making umbrellas for a living instead of being a fancy samurai. His depression and anger over his wife Oiwa’s miscarriage and subsequent illness and growing certainty that she is cheating on him with Kohei. Nothing is going right for Iemon and in Kinoshita’s version this makes him easy pickings for Naosuke, “the incarnation of evil” as he’s called at the end of Part I. But it ends up being like those adaptations of Othello in which Iago is responsible for everything Othello does, even when Othello kills Desdemona with his bare hands. Iemon tries to divorce Oiwa, but she begs him not to. He can’t bring himself to tell her the real reason, that if she will not divorce him, he’ll kill her, that he’s already tempted to. Iemon can’t leave her, but he can’t stay either. Or maybe, I should say, Iemon won’t leave her, but he won’t stay either.

If the Oiwa of Part I has mostly been a guilt-delivery system for the plot, Part II has a very different tone. Tanaka plays Osode with moxie a-plenty. She thinks Oiwa was too kind for her own good and she doesn’t plan on making that mistake on her own Osode, Yomoshichi, and the local constabulary have begun investigating Oiwa’s disappearance. Convinced Iemon has murdered her sister, Osode confronts him, despite receiving the excellent advice, “Don’t go confront a murderer.” Wearing the kimono she had given her sister, she resembles Oiwa so much that Iemon goes right into stabby madness. Meanwhile, Iemon discovers that Naosuke is not a gardener and murder friend, but a gangster and the very thief who snuck in and stole from Iemon’s old lord, getting Iemon fired. Naosuke has chatted up Omaki, Oume’s servant, and Iemon arranging the marriage as part of a really evil heist. Iemon goes along with Naosuke’s plan to steal from his father-in-law, because he’s either given up or he’s lost in his haunted world of guilt.

Once Naosuke has broken into the storehouse, Iemon tries to get Oume to run away with him, but Oume has noticed his shouting about Oiwa and has realized Iemon did something terrible. She grabs a sword to defend herself and Iemon tries to take it off her. In their struggle, they knock over a lantern and set the house on fire. Oume’s face is burned in the same place as Oiwa’s, and Iemon drops her like a hot potato to die in the fire. He turns on Naosuke and slashes Naosuke’s eye with a sword then chases him through the burning house. Omaki finds Oume and gets her to safety. While Iemon, his own face burned, kills Naosuke. He sees Oiwa in the flames, back during happier, umbrella-making times. Then we see Oiwa and Iemon reunited and enjoying cherry blossoms. Perhaps it was in their past. Perhaps it is in some heaven. But I can’t really feel Iemon deserves it. Or more, I don’t think Oiwa deserves an eternity with Iemon, even if he’s very sorry now. The next morning the neighborhood gossips. A man tells people, “Inside the flaming inferno, I heard someone’s voice crying, ‘Forgive me!’ Over and over until the building collapsed.” I guess the moral of this story is to appreciate your sweetie now, rather than after you’ve let your murder friend talk you into murdering her. Also, maybe don’t have murder friends.

Naosuke’s plan is insane and appalling. And Iemon is utterly passive as Naosuke goes forward. So what’s worse, setting up Iemon to kill his wife and marry a new lady all as part of a plan to steal her father’s money? Or just going along with the plan? As “the incarnation of evil,” Naosuke takes a lot the blame, but I don’t think that Naosuke is wrong to say that this is what Iemon wants, that Iemon does want the admiration of a young, healthy woman and that he doesn’t want to feel like a failure anymore. And so even if Iemon doesn’t know the burn cream Naosuke gives him will kill Oiwa, he still knows what Naosuke is capable of. He should have known not to trust Naosuke by then. Like Naosuke, Iemon wants what he wants. Naosuke just likes it when an evil murder plan comes together. Kinoshita’s Iemon just doesn’t want to feel bad about what he wants. And that makes Iemon pretty awful.

Japan’s Master of Horror Takes on The Worst

It’s hard to say whether his passive awfulness is more or less awful than the extremely active awfulness of Iemon in Nobuo Nakagawa’s Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan. Because there is no doubt in Nakagawa’s adaptation that Iemon is the absolute worst. Nakagawa’s Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan film was the first widescreen, color adaptation. And, holy cats, is it in color and beautifully stylized. It is shorter than both Kinoshita’s Yotsuya Kaidan and the source play, but it is remarkably faithful. The film starts as a play itself with a song about how the bond between husband and wife is eternal, asking how one could kill one’s spouse. Then it moves right into the action, with Tamiya Iemon (Shigeru Amachi) confronting Yotsuya Samon (Shinjiro Asano) and Yomoshichi’s father on a sidewalk at night and demanding he be allowed to marry Samon’s daughter Oiwa (Katsuko Wakasugi). Yotsuya Samon tells him that he’d never let his daughter marry a jerk like Iemon—and reminding him that he is the worst and that samurai care nothing for money.

Iemon goes all murderous then decides to cover it up, telling Oiwa and Osode (Noriko Kitazawa) that he’ll avenge their dad. In this adaptation, Naosuke’s (Shuntaro Emi) evil is way overshadowed by Iemon. He’s pretty much a toady. He had been a servant of Samon, but helped Iemon hide the bodies and come up with a story that a local bandit had killed the men. When Iemon sees his chance to hide his guilt and marry Oiwa, Naosuke sees his chance to make his move on Oiwa’s sister Osode. After all, Yomoshichi has agreed to wait on marrying Osode until they’ve avenged both dads.

They set out ostensibly for vengeance and stop near a shrine to the Saga brothers, who had successfully avenged their family. But the murder friend plan is to get rid of Yomoshichi at the first opportunity. Oiwa is too weak to pray at the shrine and so Osode stays with her while the men go to pray for success in their revenge. When they reach the top of a waterfall, Iemon stabs Yomoshichi as the man begins to pray and pushes him over the falls. Iemon and Naosuke then run back and tell the sisters that Yomoshichi had been murdered by the same dad-murdering ne’re-do-wells. Iemon and Naosuke decide it’s best to split up for safety, practically nudging each other in the ribs. Iemon settles down to make umbrellas and telling Oiwa he doesn’t want to hear anymore about avenging her dad. Oiwa has given birth to their son in the meantime, but she is weak. Osode takes up work in a teahouse and tells Naosuke she won’t sleep with him till her father, her fiance and her fiance’s father are avenged. Naosuke spends his time selling medicine on the street and lunging lecherously at Osode. Also, meeting Iemon for gambling at Takuetsu’s House of Ladies, Massages and Gambling.

One day, Iemon impresses Oume (Junko Ikeuchi) with his sweet intimidation through hat-doffing skills. Naosuke tells Iemon about it and the whole spiel about being on easy street once Oiwa’s out of the picture. Mr. Ito (Hiroshi Hayashi) is much more involved as well, telling Iemon that something would have to be done about his “maid” if Iemon wished to marry Oume. This Iemon is much easier to convince and even pours the poison tea for Oiwa before heading over to the Ito’s house to work out the details on his marriage and new position. He tells Oiwa he’s sent for Takuetsu so that she can have a nice massage. And Oiwa thinks he’s being romantic. Iemon tells Takuetsu (Jun Otomo) that he doesn’t want Oiwa anymore and Takuetsu should just go over and do whatever he wants. And Takuetsu, having nursed a bit of a crush on Oiwa while nursing Oiwa back to health, is interested. Except Oiwa’s taken the medicine and Takuetsu is terrified of her now. He tells Oiwa how Iemon set her up and Oiwa attacks him with a razor, cutting herself in the process. She bleeds to death. When Iemon returns home, he executes Takuetsu and briefly considers cutting the “lovers” in half, before settling on nailing them to opposite sides of a door and throwing them in the river. He has Naosuke do the nailing before they head off for his wedding.

And then the haunting begins in all its lurid technicolor glory. A ghostly and ghastly Oiwa asks Iemon how he could poison her. She appears above him on the ceiling, still nailed to the door. She floods his marital bed with supernatural river water. And she and Takuetsu trick Iemon into killing Oume and Mr. Ito. Iemon flees to the monastery on Snake Mountain, hoping to have the ghosts exorcised. Oiwa continues to haunt him there, too.

But Oiwa also causes trouble for him on the material plane. She appears at her sister’s house, creepy enough, but not disfigured, so Osode just thinks Oiwa is, as usual, feeling poorly. But Naosuke knows Oiwa is dead and he sees a more dreadful ghost with drooping eye and disheveled hair. Naosuke tells Osode that maybe he helped kill Oiwa and that maybe he helped set Iemon up with a new lady. And it’s possible that Osode already suspected since he brought her home Oiwa’s hair comb and soggy kimono that he dragged out of the river with a pretty sweet looking hook decorated with a dragon. I hope Osode got the dragon-hook in the break-up. Anyway, he thought these were excellent presents, but, hook aside, Osode recognized them as Oiwa’s. Oiwa also brings Osode and the not-at-all-dead and totally-pushed-off-a-waterfall Yomoshichi back together, so now Osode’s pretty certain that Iemon is, indeed, the absolute worst. Osode and Yomoshichi agree Iemon is the absolute worst and head out for Snake Mountain to kill themselves a horrible human being and avenge everyone else in the entire movie. Meanwhile, Oiwa really ups the haunting, driving Iemon berserk with creepy appearances, bloody water and the occasional glimpse of Takuetsu’s split head. Iemon stabs Naosuke and runs around all freaked out until he finally blunders out into the monastery’s snowy courtyard and is confronted by Osode and Yomoshichi all dressed for vengeance.

Miike Returns to the Stage

Miike’s Over Your Dead Body (2014) is most influenced by Nakagawa’s adaptation. He takes Nakagawa’s conceit of beginning the story in a theater and makes his about a theatrical production of Yotsuya Kaidan that goes very, very wrong. He’s playing with the idea of the curse that has befallen productions that were insufficiently respectful of Oiwa. Miike’s brings back kabuki actor, Ebizo Ichikawa XI, who also starred Miike’s Hara-Kiri: Death Of A Samurai (2010). Ichikawa’s kabuki lineage goes back to 1673 to the first Ebizo Ichikawa. In Over Your Dead Body, Ichikawa plays actor Kosuke Hasegawa who performs Iemon in the film’s troubled production of the play. Hasegawa’s name is a direct reference to acto Kazuo Hasegawa, who played a remarkably mild-mannered Iemon in Kenji Masumi’s 1959 Yotsuya Kaidan, aka Thou Shalt Not Be Jealous. In Masumi’s film, Iemon is not directly responsible for Oiwa’s death and attempts to avenge her. And despite Over Your Dead Body referring visually Nobuo Nakagawa’s splendidly technicolor adaptation, Miike and screenwriter Kikumi Yamagushi have some sympathy for Kosuke Hasegawa.

In Over Your Dead Body (2014), Oiwa goes from a simultaneously sympathetic and terrifying figure to something more along the lines of a woman driven insane by irrational jealousy. The actress playing Oiwa, Miyuki Goto (Ko Shibasaki) and Kosuke have a relationship, and their relationship starts to resemble that of Oiwa and Iemon. Kousuke is a player. Miyuki is hurt and jealous of the actress playing Oume. And the idea is that perhaps they are possessed by the play, that they don’t manage to keep enough distance between themselves and the story. But Miike’s whole adaptation seems like a weird misreading of the play. Sure, it’s a jerk move to cheat on your girlfriend, but it’s regular jerk, not Iemon-level jerk. And in having Miyuki begin to behave like Oiwa as a parallel when the problem is lying, cheating and not taking responsibility for a pregnancy kind of makes the story more along the lines of “women are just plain crazy.” And this is underlined when, instead of having a miscarriage as in Kinoshita’s film or giving birth and then implicitly killing her child, as in the original play and the Nakagawa film, Miyuki cuts herself open looking for the baby she believes she’s having with Kosuke. Sure it’s gory and awful but it’s also kind of boring and predictable and it simplifies more complicated material, and not in a good way. Not like the way Nakagawa condenses the play into just over an hour. It’s more like if he made a film and took every opportunity for a fart joke, if farts were much gorier and grosser.

As Miike’s work becomes more respectable, I find I like it less. It’s not that it’s lacking the inspired madness of Miike’s most famous work. He makes a beautiful film. And I admire the craft of 13 Assassins and Hara-kiri: The Death Of A Samurai, but I think I’m too familiar with the original films to really enjoy his remakes. So much of what is good in those films is Miike following after the original directors. And what is off about them is Miike Miike-ing things up. Sometimes that really works. But sometimes Miike-ing up something totally undermines it. A rape by a powerful official isn’t enough for Miike’s 13 Assassins, the villain must be cartoonishly villainous and the woman must be stuffed into a box limbless and tongueless (and realized via an awful digital effect). This undermines the film as an indictment of a brutal, oppressive and dehumanizing system and makes it about one villain and once he’s taken care of, everything’s fine. And there must also be flaming cows. I would love flaming cows in almost any other Miike film—it would’ve fit right in Sukiyaki Western Django.

Over Your Dead Body is actually one time where if he went all out with Kosuke/Iemon being awful, as awful as the Shogun’s nephew in his adaptation of 13 Assassins, and he went all out in making Oiwa’s ghost gross and spooky and her vengeance gruesome, that would work well with the material and its tradition. Back in the day, Yotsuya Kaidan was notable for its gore and effects. Oiwa pulling her bloody hair out in clumps in an impossibly growing pile. Oiwa’s ghostly face reflected in a lantern. Miike ghostly Oiwa is fantastic. But instead of going with that, Miike restrains himself, making a gorgeous and self-consciously classical film and then goes all crazypants on Miyuki cutting herself open to find her baby and attacking Kosuke to force him into a commitment. How do you turn a story like Yotsuya Kaidan into a movie that essentially shrugs and mutters, “Women, am I right”?

It’s important to be careful with stories, especially ghost stories. And Miike knows that, he’s playing with the convention that Oiwa’s story is a dangerous one to tell. That there is a history of accidents, injuries and deaths haunting theatrical, film and television productions. That the actors are in danger and that the actor portraying Oiwa is especially in danger. And I guess it’s just kind of annoying in a metafictional story about the dangers of telling Oiwa’s story, he doesn’t really respect her. And really, crazy girlfriend or no, Iemon is the absolute worst.