As a kid in the 1970s, I watched Space: 1999 fairly religiously. And perhaps not entirely unpredictably, I didn’t remember a thing about it other than the uniforms and the Eagle spaceships, the giant toy of which a friend owned and would pit in battle against my Micronauts Hornetroid. As to the actual content of any one episode, however, I drew a persistent blank despite the hours I’d logged watching it during one of its many syndicated Saturday afternoon broadcasts. I had a vague sense of it being sort of heavy, and maybe a little profound, or what passed for profound before the eyes of an eight year old. Despite being a member of the so-branded Star Wars generation, I had as a child and still have as a grown man a deep appreciation for science fiction at its most ponderous, heavy-handed, self-important, earnest, and weird. So when I had a chance, through the magic of an affordable DVD release of the series, to go back and revisit the series — or more accurately, visit it again for the first time, such as the case may be — I was quite excited.

Space: 1999 began life as a different series, the delayed second season of creator Gerry Anderson’s occasionally popular UFO. Anderson, who began his career in film and television production as an editor, was and is best known for a series of science fiction and adventure shows starring puppets and marionettes. These “supermarionation” shows became his calling card but were never his passion. Rather, he fell into it in much the same way an employee at any job suddenly inherits for life some new project: he was the guy who was around. He’d been hoping for a chance to move out of editing and into production and directing. He got that chance in 1957, when he was hired to direct a children’s puppet show called The Adventures of Twizzle, about the adventures of a group of lost toys.

He parlayed the experience into forming his own production company, along with colleagues Arthur Provis, Reg Hill, John Reed, and a woman named Sylvia Thamm, who would later become Sylvia Anderson, Gerry’s wife and the guiding visionary behind the distinctive look and fashion that highlights many of their shows. Their first production, and Anderson’s second in the driver’s seat, was 1960’s Torchy the Battery Boy. Torchy was Anderson’s first foray into science fiction, with a main character who traveled through space in a rocket and hung out with yet more sentient abandoned and lost toys. That same year, Anderson and his production company made Four Feather Falls, a Western with a rootin’ tootin’ sheriff who wrangled the unruly residents of a small Kansas town with the help of his talking horse and dog. The show was a major success, and before Anderson knew it, he was the puppet show guy.

It wasn’t bad, really. Anderson’s AP Films signed a deal with Lew Grade, president of Incorporated Television Company (ITC), whose specialty was producing British television shows with eye on distributing them internationally. Marginal success at home didn’t mean much as long as they reaped larger profits abroad. In partnership with ITC, Anderson began to work on a steady stream of science fiction supermarionette shows throughout the sixties, including Supercar, Fireball XL5, Stingray, Joe 90, and his two best known series: Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons. It was during the production of Captain Scarlet that AP Films changed its name to Century 21 Productions.

In each case, with the promise of overseas money thanks to ITC’s many deals, Anderson shot the episodes on film, as if for the movies or an American television show. This was in sharp contrast to the more common practice at the BBC of shooting on video, as was done with the science fiction juggernaut Doctor Who. Additionally, since the shows were made with an eye toward the American market more than the domestic British market, they were structured more in line with American television standards: twenty-five or fifty minute total run times and self-contained, non-serialized episodes. Again, this was in contrast to the example set by Doctor Who, where a single story could run through multiple episodes or an entire season. The end result of this style was a very high-end looking production, something ITC would implement with almost all of their series. Episodes of The Avengers or The Prisoner or the many Gerry Anderson shows looked more like movies than they did cheap British television shows.

As much as the marionette “actors,’ Anderson became known for his obsession with miniature and models special effects, designing elaborate (and often utterly impractical) vehicles, bases, and weapons systems. Although quaint when looked at with modern eyes, and not as ambitious as similar effects work being done by Eiji Tsuburaya in Japan, Anderson’s attention to detail was obvious in both the quality and quantity of miniatures and futuristic sets that were designed for the APF/Century 21 properties. Combined with the shot-on-film approach and international distribution, the plentiful effects work soon meant that ITC was making some of the highest end, highest profile, most sophisticated entertainment in Britain, competing less with the British television market and more with British film.

“What do we really know about UFOs?”

Although successful, Anderson was getting restless and feeling trapped in the ghetto of made-for-kids marionette shows. There had often been a hint of slightly darker and more mature content in his shows — Captain Scarlet begins with the titular hero accidentally annihilating an alien city — but Anderson wanted to break free entirely from the world of puppets and Penelope. He finally got his chance in 1969. It came not in the form of a television show, but as a feature film. Doppleganger — released as Journey to the Far Side of the Sun in the United States — is a dark, live-action science fiction drama about astronauts who discover a duplicate but slightly off-kilter second Earth orbiting the opposite side of the sun. It is a contemplative, slow-moving, and somewhat pessimistic film that ends in the failure and death of the main character. It also proved to Lew Grade that Gerry Anderson could handle serious, adult science fiction and live action. With Doppleganger under his belt, Anderson was given the green light on his first live action science fiction series: UFO.

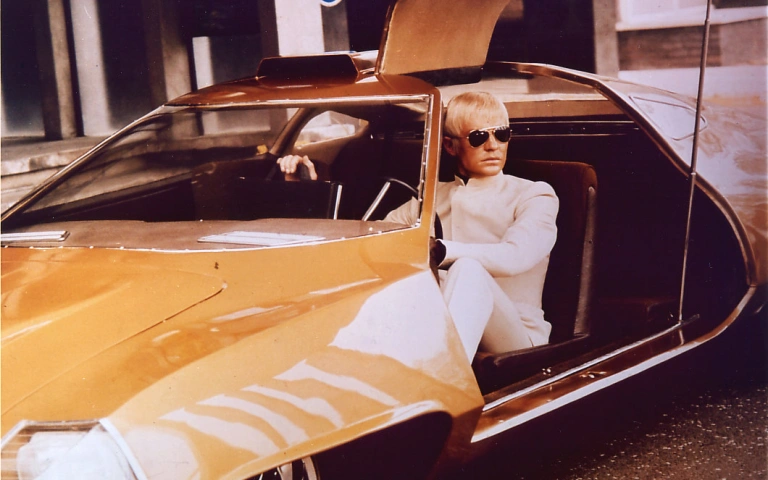

You can’t really blame viewers who sat down to watch the first episode of UFO for expecting it to be pretty much the same as everything else Gerry Anderson had done, only with live actors instead of puppets. Those misconceptions about the show were quickly dispelled. UFO has the sort of high concept that sounds like typical Anderson: a secret organization called SHADO (Supreme Headquarters Alien Defense Organization) is fighting a clandestine war with mysterious invaders from outer space, trying to protect the earth both from destruction and from any knowledge at all that these aliens exist and that we are at war with them. Heading up SHADO, and disguised as motion picture mogul, is platinum blonde Ed Straker (American actor Ed Bishop), and decorating this futuristic world in which humanity now lives is Sylvia Anderson, unfettered by the need to cater to marionette limitations and free to indulge the most candy-colored extremes of pop-art futurism and swingin’ London style.

But beneath the shiny purple hair, silver space mini-skirts, and secret bases equipped with Scotch machines was a very different sort of tone than people expected from Anderson. Straker is a very flawed human being, often threatening and aloof, willing to kill even his own employees and acquaintances if they threaten the secrecy of SHADO. The organization itself is morally dubious, with the effort to keep humanity in the dark about this threat from outer space seemingly at odds with the concept of a free and open society. Although ostensibly about SHADO fighting the UFOs, most of the episodes are about personal conflict and psychological damage. In an early episode, the competency of moonbase commander Lt. Gay Ellis (Gabrielle Drake) is called into question when a computer determines that her affection for moonbase pilot Mark Bradley (Harry Baird) might be clouding her command judgment, and Straker puts them both through a gruelling range of tests. SHADO acquires one of its star members (Michael Billington’s Col. Paul Foster) when he accidentally discovers the organization and is given the choice to basically join up or be executed.

But the two most harrowing episodes both revolve around Straker. In “A Question of Priorities,” Straker’s discovers that his estranged ex-wife has remarried, and that her and Straker’s young son has been critically injured in an accident. Straker commits a slight abuse of power when he dispatches a SHADO airship to quickly retrieve life-saving medicine from the United States, but when a possible UFO is detected on Earth, he has to make a decision: divert the SHADO plane to investigate, thus dooming his son to death, or save his son’s life and betray his obligation to SHADO, possibly putting the entire planet at risk — but only possibly. In the second emotionally gutting episode, “Confetti Check A-OK,” we see the origin of SHADO and Straker’s role in it juxtaposed with the disintegration of his marriage.

The theme of one’s commitment to SHADO destroying one’s personal life is a common thread in the series, from the mangled relationship between Mark and Gay to Straker’s ruined family life to Paul’s crumbling romantic relationship. To say nothing of Straker’s inability to go more than a couple of episodes without shoving a gun in Paul Foster’s face. It’s thematic ground that would be mined later in a variety of spy films, and it’s an especially bitter pill even when wrapped in the candy color of UFO’s set and costume design. But it’s hardly the only strain of more “adult” content than people were prepared for from a Gerry Anderson show. Adultery, recreational drug use, and torture all play roles in episodes. Broadcasting in 1970s, amidst the Vietnam war , the collapse of the Summer of Love into a maelstrom of unrest and violence, and global social upheaval and distrust of authority, there is a strong streak of paranoia running through UFO. About the aliens, about one another, about SHADO itself.

Unfortunately, the show was plagued by behind-the-scenes chaos. Seventeen episodes into production, everything fell apart when MGM-British Studios went out of business, forcing Century 21 to scramble for a new home. It was five months before production could resume. When the show returned, it was with a slightly more oddball, almost psychedelic undertone (there’s even a ouija board episode). The show was also hampered by cast changes. Actor Harry Baird, whose character had been a major part of the first few episodes, left over contract disputes after filming his fourth episode. Other actors would disappear with noticeable abruptness, especially after the unplanned five-month break when the show lost Gabrielle Drake and, even more noticeably, George Sewell who had played Straker’s second in command, Col. Alec Freeman. The confused production resulted in episodes being aired out of order and an overall sense of disjointed schizophrenia in the show. The darker, more adult nature confused and surprised viewers, and the outrageous excesses of the production sometimes overwhelmed the more mature content.

For some, Anderson’s efforts to infuse the series with adult themes are in obvious conflict with his inability to come up with a more adultly logical set-up. There is much about UFO that should have been thought through with a little more care. Chief among these would be the entire set up on the Moon, Earth’s first line of defense against these organ-stealing space invaders. Moon base has three ships, and each one is armed with but a single weapon: one missile. Which means the aliens can defeat our first line of defense simply by sending four guys. And yet the show never seem to thing this is anything but a perfectly acceptable military strategy. They also only have one jet to protect all of the earth, and for some reason it’s connected to a submarine, a submarine being possibly the least sensical vehicle you could spend money on as an organization dedicated to fighting spaceships.

After the initial run of twenty-six episodes, the series was canceled. At least for while. Two years later, the show was syndicated for broadcast in the United States and became enough of a hit that ITC called Anderson back and commissioned a second season, only with a few changes to better suit the American audiences. First, the moonbase-based episodes had been much more popular in the States than the ones set on Earth, so the new season should be set on the moon. No problem, Anderson said, and he soon presented a concept in which SHADO has greatly expanded its moonbase presence, building a vast complex and using it as their new headquarters. ITC liked the idea, but no sooner had they said, “We like that idea” than the US airing hit the weird final third of the first series. Ratings dropped, and ITC canceled the second series. Not one to let hard work on a promising idea go to waste, Anderson took the basic concept and designs for UFO 2, tweaked them a little, and presented ITC with a pitch for a new live-action science fiction series, one about the crew of a moonbase that is thrust into deep space when the destruction of the earth sends the moon hurtling off into the cosmos. Anderson called the new series…Menace in Space.

The Future is Taupe

When British television production company ITC commissioned then changed their mind about a second season of producer Gerry Anderson’s science fiction adventure series UFO, Anderson wasn’t one to let all the hard work that went into pre-production design go to waste. He tweaked the scenario a little and gave the proposed series a new name: Menace in Space. This new take on the concept would feature the inhabitants of a moon base being hurtled out into space after a cataclysmic accident on Earth blows the moon out of orbit. Unfortunately, Anderson’s sleight of hand with his idea for UFO 2 didn’t fool ITC president Lew Grade, who remained unconvinced after the mediocre performance of UFO that a new Anderson science fiction series would be any more successful.

Still determined that his armload of sketches and plans would not end up in the rubbish bin, Anderson went to Lew’s partner at ITC America, a canny move given that ITC was in the business of producing British television aimed primarily at the American market. Here, Anderson found more success, though a few tweaks were proposed to the series. It had already been agreed upon that the series would be set on the moon (the moonbase episodes of UFO had been the most popular episodes during its US run), but ITC America head Abe Mandell didn’t want to see the earth, period. Not even in the background. “Then we’ll bow up the earth” in the first episode, Anderson exclaimed. Mandell thought maybe that was a little drastic and would prove too depressing for viewers. “Then we’ll blow up the moon!” Anderson countered, and though I doubt it was so, I can’t help but imagine him doing so with a carnival barker’s cigar clamped between his teeth.

Anderson’s initial script for the pilot bears little resemblance to the eventual first episode of the series. In his treatment, aiming for a half-hour episode, Commander Steven Maddox is the boss of WANDER, a space defense organization (not unlike SHADO from UFO) based on the moon. When deep space probes detect an advanced alien civilization, it attracts their attention to us as well. Maddox is kidnapped and scrutinized, and it is eventually determined that humanity is too belligerent, paranoid, and hostile to make good galactic citizens. The aliens intend to envelop earth with a field that will prevent humanity from venturing very far out into the universe. Maddox, however, they think is cool. They return him unharmed but then use a ray to weaken the Earth’s gravitational hold, sending the moon and the inhabitants of Moon city off into space.

In London, Lew Grade insisted that since this was an American-approved project, they should be allowed to control the series (or take the blame, if it tanked). The script by Gerry and Sylvia was put on ice, and a new writer, American George Bellak was called in to write a new pilot episode. Eventually, under Bellak’s guidance, the basics of the scenario were settled on: an explosion on the moon would send it spinning away from earth and into distant space, where the stranded crew would encounter an assortment of aliens and dangerous situations. Coming in the midst of grand contemplative works of science fiction like Kubrik’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Anderson wanted the show to be more cerebral, more philosophical, and less about old Star Trek style action-adventure. Also in an attempt to garnish some 2001: A Space Odyssey respectability, the name of the show was changed. Several times in fact. Eventually they decided on Space: 1999.

Because America was going to be the primary market, ITC wanted American leads surrounded by British actors. Gerry Anderson pursued the real-life husband and wife acting team of Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, hot on American television thanks to several years of substantial success on the espionage series Mission: Impossible. Sylvia, however, did not want American leads, and if she had to settle for American leads, she did not want Landau and Bain. Her picks had been Robert Culp (I Spy) and Katherine Ross (The Graduate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid). When Landau and Bain, eager to put some distance between them and ending up typecast in spy shows, agreed to accept the parts, Sylvia’s suggestions became moot. By this time, the marriage between the two creative partners had become strained. Having her opinions on the casting of the new show dismissed only served to exacerbate the growing rift between her and her husband. By the time shooting for the first season was wrapping, George and Sylvia had divorced.

To rub salt into the wound, the new series would not turn to her for sartorial advice, despite the fact that she’d done amazing work as costume designer and style consultant on UFO. Instead, the new series turned to Austrian-born designer Rudi Gernreich, a choice with which I have no issue really, as much as I love Sylvia’s work. He was an early financial supporter of gay rights groups like the Mattachine Society (though he kept both this and his own homosexuality private) and healthy nudism. He even invented the topless monokini, a design that eventually ushered in a fad for topless nightclubs. For Gernreich, the popular notion of nudity as somehow dirty, perverse, or shameful was abhorrent. The Austrian culture in which he’d grown up boasted an enlightened, positive attitude toward these things — a trend that was suppressed and outlawed by the Nazis. With his mother, he escaped Nazi Austria and settled in Los Angeles, where he worked as a dancer and choreographer, though by his own admission he was a terrible dancer. He also got involved with costume design and, by extension, fashion.

Gernreich’s design work reflected his Austrian “physical culture” attitude, and were frequently shocking to American sensibilities, where nudity and sex were inextricably linked and shamed. Many of his creations were see-through, including the sheer bra or “no bra” bra. He used unconventional materials and is generally regarded as the designer who brought androgyny to modern fashion (a claim I think is loaded, as androgyny was quite in style during the 1920s). Androgyny seems to have been the guiding principle behind his work on Space: 1999, with which he became involved because he was friends with Barbara Bain. Where Sylvia’s work had indulged the excesses of 1960s pop art, Gernreich’s designs matched the more somber 2001influenced new series. And unlike Sylvia’s designs, which were still fond of mini-skirts and go-go boots for some of the female characters, Gernreich dressed both men and women on Moonbase Alpha identically (oh, to have seen Paul Foster in Gay Ellis’ silver mini…). The costumes were drab, dull almost, but Gernreich’s fondness for recalling nudity can still be found in the palette, which is almost uniformly taupe. At the same time, the uniforms intentionally de-sexualize the body — forecasting by a decade plus the similar “pajamas for all (except Troi)!” uniform design of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

Behind the scenes of the show, things were as rocky as they were in the Anderson’s marriage. Bellak and Gerry Anderson clashed over creative differences, resulting in Bellak leaving the series before filming even begin. ITC scrambled and hired Edward di Lorenzo and Johnny Byrne, who reworked the pilot episode script yet again, finally giving us what would become the first episode of Space: 1999: “Breakaway.” But the troubles were only just beginning. ITC had hired director Lee Katzin to helm the series, but he proved to be a nightmare on set, demanding retake after retake, shooting entire scenes multiple times often for the most inconsequential of reasons. After going over schedule and over budget, the episode Katzin delivered to Abe Mandell and ITC was deemed utterly unusable. Anderson himself scrambled to rewrite and reshoot several scenes, while Katzin’s second episode, “Black Sun,” also ran over time and budget. The temperamental perfectionist was not asked back for a third episode.

Problems were being generated as well by the curious set-up of production occurring in England but the shots being called in New York. Scripts had to be sent to New York for approval, and mandates, sometimes contradictory, would come trickling back to England, often with no time left to do a quality job on rewrites. Byrne complained that it made it impossible to polish potentially great scripts while forcing them to spend inordinate amounts of time rewriting obviously bad ones. Because studio execs were involved, the demands were often tone-deaf, insuring that Space: 1999 would be plagued by the same sort of mood and character schizophrenia as was seen in UFO. From the start, Anderson and his writers had wanted a more cerebral show, but it was a constant battle, often lost, between them and the ITC executives in New York. The endless back and forth and delays meant that Space: 1999 was often a jumble of half-baked ideas and dime store philosophy — less 2001, more stoner watching 2001.

Finally, after nearly two years in production, filming on the first season wrapped. But no one got to take a breather. It turned out that the deal Abe Mandell had made to sell the series to a network had fallen through. Now Anderson had a finished season of one of the most lavish and expensive science fiction shows in British (or American, for that matter) history in his lap, and no one wanted to air it. American networks were hesitant to buy a complete series, one in which they’d had no input. ITC, Anderson, and even Martin Landau had to go old school and do road shows, pitching syndication directly to local television stations. Among the stations that bought the syndication package was a relatively new, scrappy little channel run out of a garage near Louisville, Kentucky. WDRB-TV 41 was perhaps the greatest television channel that ever existed. Low on funds and desperate to fill their air time, they would buy all sorts of weird stuff on the cheap. It’s thanks to them that little Keith Allison got to watch Ultraman, Godzilla movies, their incredible horror movie program Fright Night (which was packed with low-budget American films as well as weird Euro-horror — I saw my first Paul Naschy movie on that program).

And then I saw Space: 1999.

A Galaxy of Stars

Sandwiched in between the final episode of Star Trek and the 1977 release of Star Wars, Space: 1999 occupies an odd bit of historical real estate and has an even odder tone of voice, though it’s easier to make sense of if you understand where science fiction was when Space: 1999 debuted. It might help explain why a group of rambunctious young sprouts, such as my friends and I were at the time, were so tolerant of what was a rather morose, talky, slow-moving show. But that’s how science fiction was at the time. The original Trek was colorful and had it’s fair share of action, but much like football, if you timed the actual action against the scenes of people sitting around saying stuff, there was far less jumping around and exploding than people recall. And post 2001: A Space Odyssey, science fiction really shed its pulp trappings and entered a period of pretty trippy, contemplative mood. This was science fiction as I knew it: sort of melancholy, a lot to do with environmental catastrophe, and not really centered on “action.” It’s why we could watch Silent Running at a birthday party and love it. and It’s why we could become obsessed with a show that seemed to feature a lot of Martin Landau frowning and speaking in a hushed monotone.

A lot of the criticism of the show — and there is plenty — tends to exaggerate many of the shows perceived flaws. Even I in this series of articles have vastly overstated the “nothing happens” claim. In fact, in most episodes, quite a bit happens. It’s just that not all of it is jumping around and exploding control panels. From the outset, Space: 1999 wanted to tackle deep philosophical questions. Often, through some combination of time limits, script rewrites, and perhaps an inconsistent quality of writing in the first place, the aspirations of Space: 1999 far exceeded its reality. But this, to me, is not a flaw. To see a story that strives for profundity and only achieves a clumsy sort of half-baked mysticism still says to me that there was a group of people who were really shooting for something more, and I can garner a lot of enjoyment out of that ambition, even when it fails to come to fruition.

Another of the common criticisms is aimed at the science of the show. Despite the “hard” sci-fi look of the show (by the standards of the time), most of the plots and much of the science surrounding them was pretty absurd. But again, this doesn’t bug me. The “science” is there in the service of the plot. Space: 1999 wasn’t meant to be particularly realistic, and it wasn’t meant to be an hour-long educational program. What education was going on was more of the philosophical musing variety than it was a lesson in physics. Complaining about the inaccurate science in Space: 1999 is like doing the same for, well, Star Trek or any of many, many other beloved sci-fi classics. Why Space: 1999 was suddenly savaged for its lack of scientific accuracy probably has to do with the fact that it modeled its look after 2001: A Space Odyssey (considered a very no-nonsense and largely realistic look at something that did not yet exist) and it aired at a time when launching space stations and missions to the moon was common, so we all knew a little more about space than we had a decade before.

But I don’t care about that. To me, Space: 1999 is about human philosophy and morality, not about scientific accuracy. I mean, an explosion on the moon sends it hurtling into space at faster than light speeds, except when they need to have an encounter, in which case the moon seems to stop for however long they need to resolve that week’s plot. It’s not as if the show isn’t being honest with its science from the very beginning. I think the fact that the show is played so deadpan, with such furrowed-brow earnestness, and such an air of serious melancholy, that people expect every aspect of it, including the science, to be as serious as the rest.

In revisiting the show, I found that the flaws that were not apparent to me as a kid are glaringly obvious. I also found that they don’t really matter. They are something to make a joke about, but it’s a joke made with warm regard for the source material. It certainly has its quirks, and some of them are of such a nature that I’m never really puzzled when someone says they don’t like the show. It works so hard to me adult, to mean something, but also operate within the confines of Saturday afternoon kids’ fare. That’s a dubious razor’s edge to try to balance, and I think the show succeeds most of the time. It’s a very depressing show to be aimed at kids, and one that breaks from traditional science fiction about space exploration.

The Alphans are not well-trained military officers prepared to face the unknown. They are just people, totally out of their league and struggling to deal with a situation none of them could have ever conceived. For them, space is a place of wonder, but it also a place of incredible danger and uncertainty — very much a reflection of feelings about the real world at the time. Star Trek faced its fair share of incredible alien threats, but they always did it with the bright, gung-ho energy of a positive thinking force with no doubts about itself. The Alphans, by contrast, are constantly wracked with self-doubt. The excitement of exploration is tempered by the fact that none of them are explorers, and none of them are trained for the things they will now face on a weekly basis. The optimism of Star Trek has given way to the uncertainty that come from an era of Vietnam War fallout, terrorism, gas rationing, and upheaval. If we as kids wanted to be Captain Kirk, it was more likely in the end that we would actually be Commander Koenig.

One of the other things I love about revisiting the show is seeing so many faces that are now familiar but were, in 1979 or 1980 or so, unknown to me. Space: 1999 benefitted it seemed from the collapse of the British film industry in the 1970s. This collapse left a lot of A-list actors scrambling for work, and that means that a show like Space: 1999 was suddenly able to afford to hire some of the most recognizable faces in British cinema. Everyone from famed Hammer stars to new British cinema up-and-comers such as Ian McShane pop by. And Patrick Mower, of course, as a space cowboy! I thought, by way of exploring the show a little more, I might concentrate on some of the first season episodes featuring the most notable guest stars. And the first episode, of course, because it’s the first episode.

Breakaway

Despite its lack of an alien menace, everything you need to know about the tone of the series can be gleaned from the pilot episode. It’s a slow-moving mystery episode characterized by an almost drab appearance — the sort of outer space that looks like people live in it, rather than the shiny candy-colored future of Star Trek (which itself would show the influence of Space: 1999 a couple of years later, when the first Trek movie debuted and featured a Starship Enterprise and Federation uniforms that were much more monochromatic and drab than the ones we’d last seen on television). Although the concept of “lived in” outer space as an artistic trend in science fiction is often attributed to Alien, Space: 1999 played a role in developing that aesthetic (and was itself doubtless influenced by Solaris, with its littered space station and astronauts sitting around in their underwear).

“Breakway” introduced us to our principals: Commander Koenig (Martin Landau), Dr. Helena Russell (Barbara Bain), and Prof. Victor Bergman (Barry Morse), sort of the Kirk, Spock, and Bones of the show; and the second level Sulu/Scotty/Chekov in Paul Morrow (Prentis Hancock), Alan Carter (Nick Tate), and Sandra Benes (Zienia Merton). Although the show would become know for a series of strange alien antagonists, for the pilot episode the primary thorn in the side of the Moonbase Alpha crew is an inexplicable, deadly disease and a totally explicable, obnoxious visiting politician (Roy Dotrice as Commissioner Simmonds). Eventually, the disease is traced to a faulty nuclear waste dump, and Koenig and the Alphans must scramble to repair it before it results in something disastrous. As was often the case in Space: 1999’s predecessor, UFO, and as would also frequently be the case for Moonbase Alpha, they do not succeed.

A slow burn mystery for much of the run time, but full of more than enough cool special effects and 2001-inspired space stuff to keep one’s eyes occupied. Rather than feeling adventurous and vast, Moonbase Alpha feels claustrophobic and fragile — a tiny bubble of safety stranded in the harshest of environments. The acting is indeed understated, but it’s not bad at all. It’s actually a welcome breath of fresh air to return to a series that speaks in a soft tone, now that we live in an era where science fiction shots rather than speaks, and seems constantly to be banging pots and pans together like an attention-starved child. I like Simmonds as the scummy, self-serving politician — something else you would not have seen on Star Trek but makes perfect sense for a show that grew out of the Watergate era, when faith in the institutions of government and authority was shattered. It’s a pretty good start to the series.

Earthbound

Guest Star: Christopher Lee

Because Space: 1999 aired in syndication, the original intended order of episodes bore no resemblance to the order in which they aired on individual local stations. “Earthbound” would often show up in the middle of the series, which made little sense since it features a main character from the pilot episode (the selfish politician Simmonds) who only appears in “Breakaway” and this episode. So for some, a main character was introduced, then promptly disappeared, only to resurface out of nowhere to once again become a main character. “Earthbound” makes perfect sense as a follow-up episode tot he pilot, however, or at least one set very close.

At the end of “Breakaway,” Koenig solemnly announced that there was no hope of ever returning to to Earth, and that the moon and Moonbase Alpha’s three-hundred or so inhabitants were fated to be forever wanderers with no control over their destination. As we pick up the story in this episode, everyone is pretty depressed about that — at least until they encounter an alien spaceship. First contact is handled well, with a perfect mix of apprehensive dread and excited wonder. Koenig and his away team find a small group of aliens, seemingly dead, inside pods. But they’re not dead at all, actually, at least they aren’t until the clumsy poking around of the humans ends up killing one of the sleeping aliens. The other aliens revive, and though things threaten to get nasty when they discover the humans, cooler heads prevail and the death is chalked up to unfortunate misunderstanding.

It turns out that the aliens, the Kaldorians, are refugees from a dying planet. They have determined that, in all the galaxy, Earth is the most compatible world for them. So using suspended animation technology, the small band (led by their captain, Zantor — Christopher Lee, at his most solemn)of survivors set out in hopes they might be able to peacefully settle down on Earth. It also turns out that the hibernation pods are compatible with human physiology, though some preparatory work is required beforehand. This is good news for the frayed nerves of the Alphans, who suddenly have a chance to return home. Except that, Zantor regretfully explains, his ship is tiny. The unfortunate death of a crewmember means one slot is open, but only one. Who among the Alphans should be chosen to accompany Zantor and the Kaldorians on the sojourn to Earth?

Space: 1999 frequently featured hostile or inscrutable aliens, but here we have perfectly friendly aliens who want to help out. The threat for this episode comes from Alpha itself, and the emotions of the crew confined to a hopeless fate that suddenly have an out. Koenig is determined that the base computer will analyze prospective candidates and make the final decision, but not everyone is happy with that. Characters we know to be otherwise decent are suddenly motivated by desperation — or by hope — to behave erratically, even selfishly, but with very understandable motivation. However, no one is more of an asshole about it than Commissioner Simmonds, who bullies everyone, blusters, and in the end is willing to put the entire station at risk in order to make sure he is the one to accompany the Kaldonians.

“Earthbound” is a pretty intense episode, no less for the very good twist at the end. Space: 1999, like UFO before it, does not shy away from portraying its protagonists as flawed, and this episode really brings that to the forefront while still maintaining sympathy for everyone. Well, almost everyone. Simmonds is just a horrible human being. As Zantor, Christopher Lee has little to do but solemnly announce his lines and look somewhere between regal and utterly ridiculous in the get-up they have him wear. But then, Christopher Lee was no stranger to silly costumes. Although relatively reserved, he still brings his usual air of confidence to the role, a stark juxtaposition to the nerve-wracked, confused, and sometimes selfish Alphans. New age crystals and silly silver wigs aside, it’s quite a good episode with a really biting final scene.

Missing Link

Guest Star: Peter Cushing

Having had their brush with Dracula, it was time for the Alphans to meet up with Dr. Frankenstein. Peter Cushing stars as Raan, a scientist from an advanced alien civilization that lives in a city that looks like something mustachio’d Alan Paul might airbrush onto the side of his custom Eagle, the one with the waterbed and sweet hi-fi that he uses to try and seduce Sandra. An accident with one of the Moonbase ships leaves Koenig in a coma, and while Helena and Victor debate over whether to keep him alive on a machine or let him pass away, we know that his consciousness is really being held prisoner by the curious Raan, who thinks that humans might be some sort of missing link in the evolution of his own people.

To prove this hypothesis, Raan subjects Koenig to a battery of strange hallucinations and tests that, frankly, don’t seem to have anything to do with proving Raan’s point. While in this strange parallel dream world, Koenig meets and, through sheer force of his blandness, charms Raan’s daughter, who is distressed by the increasingly dangerous tests through which her father wants to run Koenig. Meanwhile, back on Alpha, tempers flare over the fate of Koenig’s body, with Helena wanting to put the poor man out of his misery while Eagle pilot Alan is ready to punch anyone who tries to turn Koenig’s breathing machine off.

Although Raan seems to be a pretty terrible scientist, Peter Cushing is a very good actor, even under gold face paint and a silly quilted cap. He plays the alien scientist with the same sort of amorality he brought to Frankenstein in the Hammer horror movies. Raan isn’t evil. He simply thinks in a way that is totally incomprehensible to humans. The things that are important to humans are not important to him, and he cannot understand why Koenig would object to his new role as an abused lab rat. Where as Christopher Lee played the role of Zantor with a regal reserve, Cushing is equal parts charming and menacing, friendly and deadly.

One thing Space: 1999 tried to do with a lot of its aliens is break away from the notion that they are basically humans but with weird faces. They conceived of everything as we did, however. Space: 1999 frequently tried to write aliens that had entirely alien ways of thinking, ways that brought them into conflict with the Alphans not because one side was good or evil, or right or wrong, but simply because they were so different — something we see even today between cultures that conflict. Peter Cushing’s Raan is one of their bigger successes, and I think that’s partly because Cushing was familiar with the type of role. The subplot, in which everyone fights over whether or not to unplug Koenig, is less successful because the motivations and decisions seem to flare up out of nowhere. But that’s easy to ignore since the bulk of the episode is so good. Heck, Koenig’s psychedelic hallucination sequence alone is worth the price of admission.

Death’s Other Dominion

Guest Star: Brian Blessed

Ahh, Brian Blessed. Or maybe I should say BRIAN BLESSED!!! He’s an actor best known for the fact that his whispering voice is a barrel-chested bellow. He roared and rumbled his way into the hearts of cult film fans thanks to his role as the boisterous Voltan, prince of the Hawkmen in the lavishly campy Flash Gordon, and as King Richard in the first season of Blackadder. I was anxious to see how a man best known for his inability to do anything but shout would fare wrapped amid the substantially more reserved style of Space: 1999. Sure, people would yell at each other on occasion, but for the most part, Moonbase Alpha maintained the “shhhh” of a moderate size library.

It turns out that Brian Blessed is actually a classically trained actor who, despite thunderous gusto being his trademark, is capable of playing it subtle when he needs to, or at least subtle for Brian Blessed — which brings an extra energy to his character, a sort of barely contained energy that translates into a charisma and electricity that is to the benefit of the episode. When Alpha detects a signal from a passing ice planet, Koenig leads a woefully ill-prepared landing party to the surface to investigate. After wandering aimlessly for a few minutes in Arctic conditions, everyone is just about dead until they are rescued by some locals. The locals, it turns out, are led by Dr. Cabot Rowland (Blessed). They are remnants of an old Earth exploration ship that crashed. Oh, and they are immortal.

Once safe in the ice caves of the planet, called Ultima Thule, Koenig and his team start thinking this might be an OK place to settle. Because somehow, living in a small ice cave on a nightmarish planet of cold, constantly being badgered by a loud crazy guy who capers about and recites bad poetry (John Shrapnel as mad Jack Tanner), is better than staying on Alpha where they at least have temperature control and no mad Jacks. But, as would frequently be the case with the series, the episode tries to sell us this hellhole as some sort of paradise, especially since everyone lives forever. Victor, who is supposed to be a man of science, almost instantly buys everything the burly Dr. Cabot Rowland sells him, but Koenig is suspicious that there might be something more to this immortality business, something sinister. He’s correct of course.

“Death’s Other Dominion” is meant to be an adaptation of the novel Lost Horizon, in which the survivors of a plane wreck discover the lost city of Shangri La and it’s advanced, immortal inhabitants. It’s a pretty good version of the story (certainly better than the 1970s movie Lost Horizon), and as with “Missing Link,” it succeeds largely thanks to the force of its guest star. Blessed exudes a weird combination of warmth and menace, and it’s easy to understand how the weary Alphans might be swayed or subtly threatened into going along with his scheme, which includes a newly immortal human race fanning out across the galaxy to become and spread enlightenment. If there is a flaw to this episode, it is how intensely irritating Jack Tanner can be. I kept hoping Alan would show up out of nowhere just to punch the guy in the face. Overall, though, it’s a great episode with another good melancholy twist at the end.

Mission of the Darians

Guest Star: Joan Collins

Coming near the end of season one, “Mission of the Darians” is an ambitious, big episode with less of a claustrophobic feel but still plenty of hopeless melancholy, as if the vacuum of space itself was actually woven from pensive sighs and a sullen vampire teenager’s LiveJournal. When Alpha picks up a distress call from a gigantic spaceship, Koenig and the usual bunch (Victor, Alan, Paul, Helena,and a guy we’ve never really seen before, so we have someone to kill) hop in an Eagle to go investigate. After gaining interest to the ship, they find it seemingly derelict, strewn with trash and, oddly, overgrown with weeds and vines. Helena and the random cannon fodder guy stay behind while everyone else goes out exploring. And then things get really strange.

Helena and the other guy (I think his name is Bill) do a little snooping of their own and soon discover a group of what appear to be stone age dwarfs. Further snooping leads to Helena and Bill being captured by an entire stone-age gang, complete with loincloths and a tendency to make human sacrifices of nameless Alphans who just showed up for their first (and last) episode. Meanwhile, the rest of the Alphans get split up, with some being pursued by someone in a big silver spacesuit while Koenig meets a bunch of people in the requisite shimmering robes and Ziegfeld Follies headwear that symbolizes an advanced alien race. The are the Darians, and among them is their sort of princess, Joan Collins.

It turns out the Darians are the last survivors of a cataclysm that devastated their city-ship. the distress signal was actually centuries old. We, of course, know the Darians are lying, since Helena is already hanging out with other survivors, who have taken her taupe unisex onesie and put her in a leggy cavewoman number. And Alan is himself running wild through the station, jumping through doors and punching or shooting anything that comes near him. Koenig, meanwhile, finds that the Darians’ story of their survival collapses pretty quickly. They are a sterile race, with their DNA stored on what looks to be a Connect Five full of Jolly Ranchers. They play the role of gods to the stone age brutes elsewhere on the ship. Oh, and they have a pretty sinister diet.

Something about “Mission of the Darians” makes it feel bigger than other episodes. The sets, while cheap, convey a much more mammoth environment than we are used to seeing on Space: 1999, and a huge world-ship with multiple societies gives the episode a more sprawling feel. We have, once again, an alien race that is not evil so much as it is desperate and confused. And we get a much more active Alphan mission than is often the case, thanks largely to Paul and Alan just going ape and cold shooting and punching anyone and everyone and leading revolutions (provided you define a revolution as a small group of people walking determinedly down a hall). It’s also another episode that explores the very real emotions of the Alphan crew. Rather than being generically stoic or brave when she’s about to be sacrificed by a bunch of space cavemen, Helena is terrified. She cries. She whimpers. She acts pretty much like anyone would, which is not the sort of thing, again, people were used to seeing in science fiction.

As the Darian Kara, Joan Collins has little to do besides look beautiful and ornately dressed, but she carries herself with the royal haughtiness for which she is known, and that works so well for a character who is part of a group that is so sure of their own superiority that it never even occurs to them they might be evil. She’s also one of the few people to have done time as a major character on both Space: 1999 and Star Trek (the classic “City on the Edge of Forever”). Script writer Johnny Byrne said he was inspired to write this episode (his favorite of the series) by the then-recent story of the plane crash of the Uruguayan rugby team in the Andes Mountains, most famous for the grisly bit about survivors turning to cannibalism. Also at plays are themes of eugenics and a “master race (it’s not an accident that Darians rhymes with Aryans). I agree with Byrne. It’s one of the strongest episodes of the entire series, and for my money, one of the best hour of science fiction television we’ve had. And man, does Koenig get mad!

Once More, With Feeling

Space: 1999 had a rocky season one, plagued by an awkward production split between New York and England. By the time the show eked out a place for itself on television in the United States, Gerry Anderson was enthusiastic about beginning work on the second season. But a second season was no guaranteed thing. The failure of ITC to successfully sell the first season to a national broadcaster meant ratings were not what they could have been. And while Space: 1999 toys found their way into the rooms of many kids, the series just hadn’t caught on the way its producers had hoped. Plus, the turmoil between Gerry and Sylvia Anderson came to a head as the first season finished filming. Sylvia, who had been instrumental in the production, design, and writing of every series for which Gerry was known, left both Space: 1999 and her husband once the season wrapped. But Gerry kept at it, and in the end, he won a second season for the show. However, he — and fans — would soon discover that the second season was to be very different indeed from the first.

Other than the long wait since the end of season one, there was little in “The Metamorph,” the first episode of Space: 1999’s second season to clue you into just how much had gone wrong with the series, and how much more wrong was waiting on the horizon. Certainly, some things had changed. For starters, there’s a new theme song and someone must have found a box of colorful orange and blue jackets in a closet somewhere, because everyone has started wearing jackets. But you know how fashion trends are, and the sudden appearance of jackets is of no real concern (and I like to think inspired Jean-Luc Picard, who took five seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation before he found a jacket). Alphans have also started wearing ID badges with their name and photo on them because…in a confined space for years with three-hundred or people or so, I am sure it was awkward for Koenig to still not know “that one guy’s name.” So he issued the command for “Hello My Name Is” tags to save everyone discomfort at parties.

With a script by season one regular Johnny Byrne, direction by the accomplished Charles Crichton (who directed lots of episodes of The Avengers, Man with a Suitcase, and The Protectors), and time enough to develop the concept behind the episode, “The Metamorph” is one of Space: 1999‘s stronger episodes. We’re on pretty firm ground here: the Alphans stumble across a seemingly inviting alien entity that inevitably harbors a nightmarish secret. In the case of “The Metamorph,” the entity is Mentor (Brian Blessed, trading in the furs of “Death’s Other Dominion” for a lot of glitter, satin, and hair frost), who happens to need organic brains to power the supercomputer he’s building. The only hope the Alphans have of surviving the encounter is Maya (Catherine Schell), Mentor’s daughter. Unfortunately, she doesn’t seem to be interested in believing the horrifying truth about her father.

“The Metamorph” deals out a lot of the moral challenges and philosophical debates that were familiar from the first season, though they are this time clad in bright jackets. Central to the plot are the concepts of slavery and the inability — or unwillingness — of someone to see evil in someone they admire and love. And as was common in the first season, no easy outs are afforded the characters, no last-second ways to get out of having to decide between a terrible option and a miserable option. Most of these decisions fall upon Maya, who here has not yet been transformed into the two-fisted science officer she would become. But the strength that would emerge is still here, even beneath the surface of a confused and morally tormented young woman. Catherine Schell handles the material superbly.

As enjoyable as the episode is, and as valuable an addition to the cast Schell would prove, other things about the episode are a little odd. Most noticeable is the absence of Paul (Prentis Hancock) and even more so, Victor (Barry Morse), both essential members of the cast. But then, Space: 1999’s first season established the ensemble nature of its cast. While it’s a little strange that you wouldn’t see two of its main supporting characters in the first episode of a much-delayed second season, it also wasn’t completely suspicious. One simply assumes that in the next episode, Victor would be back claiming every horrible planet of fire made of acid across which they stumble was perfectly fit for colonization while mustachioed Paul walks out of his blacklight-lit room in a haze of smoke, sees Maya, and asks “who’s the new chick?”

No, despite a few different things, nothing in “The Metamorph” feels overly different from the first season, which had ended on a high note with some really spectacular episodes. “Mission of the Darians,” “Dragon’s Domain,” and “Testament of Arkadia” closed out the first season and showed the series really hitting its stride. there were certainly bumps along the way, but those final three stories were the most fully realized of the show’s dream of being serious, philosophical mainstream science fiction. Taking what they had done and building on it, refining it, seemed the right direction, and with “The Metamorph,” it seemed like the show was going to do just that.

But that was not the case.

A Fate Unknown

The marriage between Gerry and Sylvia Anderson had been strained during the making of Space: 1999’s first season. It, and their long and fruitful creative partnership, was over by the time that season wrapped. Her contributions over the years to their many productions was substantial, but in the end they were Gerry’s properties so she announced that she was leaving both her husband and the Space: 1999 team. Although her name is rarely mentioned as often as her husband’s the contributions of Sylvia to the Anderson output should not be underestimated. She was integral to the success of the series (or whatever meagre success it achieved), and her departure from Space: 1999 was a major blow. But it was hardly the only obstacle thrown into the show’s path.

First and foremost was the fact that the show just hadn’t done very well. The ratings were disappointing, and the production itself, spread across two continents in a time before email or other rapid forms of communication, resulted in constant headaches, delays, and budgetary strain as scripts had to be shipped back and forth between England and the United States. While Anderson and series writer Johnny Byrne set about planning and writing the second season in the fall of 1975, ITC set about seeing that there was no second season. Initially, it seemed like things might be salvaged. The problem with the trans-Atlantic writing was “solved” when Anderson hired American Fred Freiberger to oversee the scripting of the series.

This move did not sit well with ITC America head Abe Mandell, who was suspicious of Freiberger’s infamy as “the guy who writes the terrible last seasons of dying shows.” It was Freiberger who had overseen the third and final, laughable season of Star Trek, a science fictions how which, like Space: 1999 had been canceled before rallying to one more season. Star Trek season three remains notorious for the number of risible episodes it contains — crowned, perhaps, by “Spock’s Brain.” As many clunkers as the season offered up though, there were a number of interesting and philosophically ambitious — if not well-realized — episodes, so in the end, Anderson remained committed to the hiring of Fred Freiberger to save the second season of Space: 1999. It all became moot though, when ITC President Sir Lew Grade, angry about low ratings and the failure to sell the series to a broadcast network, pulled the plug on everything. Space: 1999 was dead.

But Anderson was persistent if nothing else. Undeterred, he and Freiberger fought tooth and nail for the series, pitching to ITC the addition to the regular cast of a shape-shifting female alien. Such a character, named Maya, would shake up the formula and provide for some emotion other than the sighing fatalism and stony-faced reserve of the first season. Maya, played by Catherine Schell (who had appeared in one episode of the first season as well as the Hammer Studios science fiction adventure Moon Zero Two), might have been the “Mr. Spock” of the Space: 1999, but she didn’t share his cold, logical personality. She was curious, quirky, romantic, and even enjoyed a good joke. And when it turned out that one of the first season’s main characters, Barry Morse’s Victor “We should colonize this hellish planet of ice that shoots poisonous bees at you” Bergman, would not be returning, the plans for Maya’s character were expanded, turning her into Alpha’s science officer.

Eventually, Lew Grade relented, but Maya was only the first of the changes to be demanded. The second was that the denizens of Moonbase Alpha needed to liven things up a bit and show a little more emotion, happy and sad. The most notable manifestation of this dictate is that the hinted at romantic feelings between Koenig and Helena became an overt and acknowledged relationship. For the most part though, this newfound “passion” would manifest itself as Commander Koenig yelling at people for no real reason and with little dramatic provocation. Sort of like seeing a bad production of a Shakespeare play, where the actors think intensity just means hollerin’ your lines. It’s not that Koenig was averse to showing emotion in the first season; it’s just that those outbursts were rare and scattered among scenes of him staring morosely at a wall or a beige sofa. In this episode, anyone who interacts with Koenig gets about two lines before he just hauls off and starts shouting and waving his arms around like a madman.

Star Trek, Season Two Part Two

Barry Morse left the series due to a combination of salary disputes and the desire to do something a little less chaotically run. Also gone from the second season was series regular Prentis Hancock as mustashio’d Paul Morrow. The disappearance of these main characters is never explained in the series, which just goes on as if nothing has happened. One can safely assume, however, that Victor declared a planet made entirely of sentient, psychotic razorblades to be perfectly colonizable and stayed behind, while Paul simply got in an Eagle one day, cranked up “Freebird,” and flew off into the vastness of space. There had initially been plans to drop Nick Tate’s Alan Carter from the show as well, but that alteration was reportedly heavily criticized by the fans when they heard, resulting in Alan being saved. While Zienia Merton’s Sandra also returned for the second season, it was in a much reduced capacity than her role in season one, and she would frequently not appear in an episode at all.

The number of high-profile guest appearances was also scaled back. There’d be no one on the level of Joan Collins, Christopher Lee, or Peter Cushing in the second season, though Brian Blessed would return and fans of British genre films would recognize names and faces like Patrick Mower (Cry of the Banshee, The Devil Rides Out), Sarah Douglass (The People that Time Forgot, Superman II), Kathryn Leigh Scott (Dark Shadows), and of course Patrick Troughton, the second actor to play Doctor Who. Still, these were all recognizable character actors more than they were guest stars.

To make up for all the disappearances, the show added an additional main character, Tony Anholt’s Tony Verdeschi, who appears on Moonbase Alpha with as little explanation as Paul and Victor’s disappearances. in keeping with the mandate that the show be a little less stoic and reserved, Tony is a more hot-blooded character. He’s not as good at punching things as the dynamic duo of Paul and Alan however, so instead Tony settles on immediately becoming Maya’s boyfriend, which I guess isn’t a bad settlement. As the head of Alpha’s security, he fulfills the role that “head of security” has fulfilled since time immemorial: getting beat up and thrown around a lot. In fact, more times than not, it’s Maya who has to step in and karate kick a villain or turn into a lizard monster to grapple with the alien menace of the week while Tony lies prone on the floor.

Freiberger also led the series away from its more sombre, challenging, and contemplative original mission and turned it into a sometimes unbalanced mix of speculative and action sci-fi. While fans of the first season would prove dissatisfied with these changes and lay the blame for “ruining” the show clearly at the feet of Freiberger, the reality of the situation was, of course, much more complex. Freiberger was charged with bringing a dead show back to life, with demands from producers, Gerry Anderson, and fans all having to be juggled alongside the need to make the show more attractive to new viewers. Sometimes, these disparate goals would simply be contradictory to one another, and the sad reality of production was that more times than not, Space: 1999 had to sacrifice what was admirable on the altar of what was pragmatic.

Under Fred Freiberger’s guidance, the show was jazzed up visually as well. The unisex taupe jumpsuits that had been the costuming manifestation of the series philosophy were accessorized by colorful jackets, turtlenecks, and in the case of many of the female Alphans, replaced entirely by knee-length skirts and go-go boots, like someone was rooting around the Moonbase attic and found a bunch of old clothes that used to belong to Lt. Gay Ellis and Col. Paul Foster. It looks like they also toned down the size of the flares and the height of the platform heels, at least on the men’s shoes.

Chief among the critics of Freiberger’s transformation of Space: 1999 into Star Trek: Season Three, Part Two was Martin Landau himself, though just about the entire cast was unhappy with the scripts they were receiving. If scripts from the first season had been occasionally half-baked, at least they’d not lacked ambition. Under Freiberger, the metaphysical contemplation on man’s place in the universe, on survival, on the vastness of space was replaced by action and, more odiously, jokes. Landau, whose Commander Koenig was already established as an intense and brooding individual, couldn’t believe how often Freiberger expected to end an episode with everyone gathered int he command center, recounting the lesson they’d learned that episode, then sharing a joke or a laugh. When confronted with the script for the episode “All that Glisters,” Koenig reacted by scrawling on it the comment “All the credibility we’re building up is totally forsaken in this script.” Other choice criticisms were written throughout the script.

Conflict between Landau and Freiberger continued to dog the production of season two. Whereas Landau had gone to great lengths to promote the first season, the concept of which he believed in with all his heart, he refused to do any promotional work for Freiberger’s second season, which Landau dismissed as absurd and a betrayal of the show’s values. In order to cut down costs and work within the now truncated production timeframe, episodes were filmed simultaneously. One script would focus on Barbara Bain with minimal appearances by Martin Landau, while the other script would focus on Landau with minimal appearances by Bain, allowing the two stars to work on multiple episodes at the same time. The job of balancing out the reduced role of one or the other of the stars fell upon Schell, Arholt, and Tate, who must have been scurrying between sound stages with alarming frequency.

Despite escalating tensions and widespread dissatisfaction among the cast and writers with Freiberger, season two managed to limp to completion. In December of 1976, director Tom Clegg wrapped photography on an episode titled “The Dorcons.” Although no one knew it at the time, it was the last episode of Space: 1999 that would ever be made. As with the first season, reaction to the second was mixed, though this time it was primarily over whether the change in tone had saved or destroyed the series. Once again, Space: 1999 failed to find dependable broadcasting anywhere outside of Canada. It would air unpredictably in the United States, at different times, and not in the correct order. Ever hopeful and/or stubborn, Anderson began planning on a third season and, as audience feedback rolled in and they discovered how beloved Maya became, a spin-off series about her (which, sadly, would mean she wouldn’t be in Space: 1999 season three). But even the mighty Maya and a lot of cool toys couldn’t save the series from a second trip to the scrap heap. As ratings and interest fell, so too did the axe. And this time, there would be no reprieve. Space: 1999 was finished.

Unfortunately, like the third season of Star Trek, when Space: 1999‘s second season was bad, it was phenomenally bad, sometimes indescribably bad. And sadly, memorably bad, more memorable than when it was good. Not even the best of episodes could make a viewer forget something as rancid as “Brian the Brain.” Despite its sullied reputation (it’s not like the first season had a good reputation), there are a lot of good, and a few great, episodes in the second season. “The Metamorph” is a strong start. “The Dorcons” is a strong finish, and one that revives the moral conundrums and difficult decisions so often encountered during the first season. There are times when, despite all the friction between Freiberger and the cast, season two strikes a really effective balance between the contemplative and the action-oriented. And while we on Earth may be left wondering whatever became of those poor doomed souls on Moonbase Alpha, I think we can all rest assured that somewhere out there Commander Koenig is implementing a horribly thought-out plan that will require Maya to save everyone. If that’s the future in store for mankind, well, at least we have Maya.

Special Bonus Epilogue: Aliens are Jerks: Carol Borden writes about Maya and Space: 1999’s tendency to present just about every alien besides her as super-powered assholes who want to mess with and/or destroy the Alphans simply for the hell of it.