The fake true story behind the espionage case that rocked Norway

I won’t pretend to be well versed in the particulars of recent Norwegian history. There was, what? Some trolls, and then black metal, and I think something about guys in horned helmets, only they never actually wore helmets like that. Then Ernest Borgnine hollered and jumped in a pit full of rabid dogs while waving around a couple battle axes. And that brings us pretty much up to the modern era, right? So I confess my ignorance up front, but also have done my best to rectify it somewhat, at least as pertains to the subject of Norwegian Ninja, which is Norwegian Cold War espionage during the 1980s. That’s a pretty great topic anyway, so I was happy to study up a little.

The primary joke underying Norwegian Ninja is that it’s a true story. Central character Arne Treholt is a real person, which people probably know if those people are Norwegian. He was a member of the Norwegian Labour Party and, in 1984, was arrested and convicted of espionage and treason after being accused of passing confidential data to agents of the KGB. The trial was sensational not just because it came at the height of Cold War paranoia, but because the evidence against Treholt was considered by many to be shockingly flimsy, if not totally non-existent.

Regardless of the questionable evidence, Treholt was found guilty and sentenced to twenty years in prison, only eight of which he served before being pardoned. Accusations continued to be made that most of the damning evidence against Treholt was fabricated or planted by antagonistic intelligence organizations. Criticism of the quality of the prosecution even caused the case to be re-evaluated in the fall of 2010. It’s likely this flare-up in interest surrounding Arne Treholt is what got Norwegian Ninja made, though writer-director Thomas Cappelen Malling takes a quirky approach to recounting the history of Norway’s most notorious “traitor.” As imagined by Norwegian Ninja, Arne Treholt was actually the commander of an elite top-secret special force of ninjas who answered only to the king of Norway. After endlessly irritating Stay Behind, an anti-Communist black ops organization with close ties to the CIA, Arne and his band of ninjas were either framed for treason or murdered.

I have no idea how I heard of Norwegian Ninja. Perhaps appropriate to the subject matter, awareness of the movie simply popped into my head with no external stimulus, like the world knew that I needed to know Norwegian Ninja existed, and the cosmos took whatever metaphysical steps were needed to enlighten me. There it was all of a sudden on my television, and I was happy.

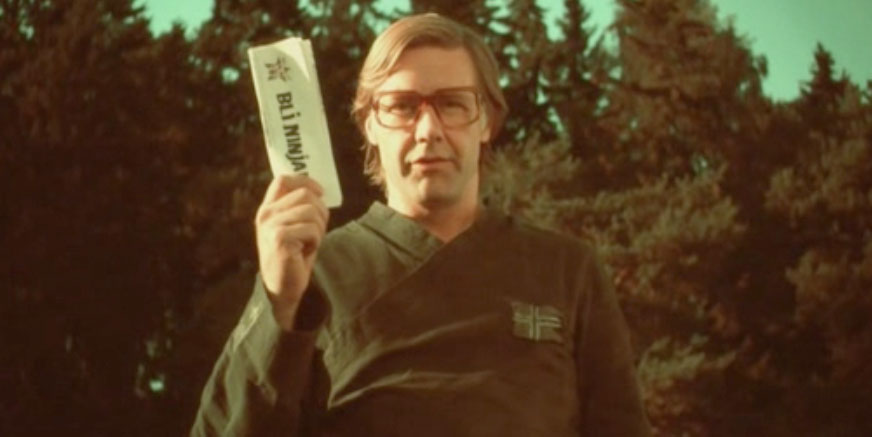

To tell this bizarre “secret history,” Malling uses a variety of techniques that give the movie a documentary-like feel, including the use of authentic archival news footage. He also gives the film a slightly faded, grainy appearance similar to what you got from old Jacques Cousteau documentaries or the covers of VHS rental tapes that had been on display in the store window too long and had become sort of yellowed and washed out. Malling also uses a clever and mostly convincing combination of CGI and charmingly crude miniatures dangling from wires to give the film its old school look.

Arne’s Ninja Force lives on a pastoral wooded island where they commune with nature, meditate, study ninjitsu, and sometimes swing into action to protect Norway from enemies both foreign and domestic. Particularly irritating to the laid-back but effective ninjas is Stay Behind, headed up by failed Ninja Forcer Otto Meyer (Jon Oigarden). Otto specializes in committing acts of terrorism that are then blamed on the Soviets, so that Norwegians will go along with whatever policy the United States wants them to adopt. From Arne’s point of view, being loyal to Norway doesn’t mean kowtowing to the United States, nor does it mean being mindlessly hostile toward the neighboring Soviets. When Arne meets a couple of Soviet agents to apologize for Norway’s freak-out over some phantom Soviet subs (most of which was staged by Stay Behind), Otto sees it as an opportunity to frame the ninja for treason, getting Arne out of the way so Stay Behind can pull off a series of dramatic terrorist attacks that will galvanize public support for a more aggressive anti-Communist approach.

Stay Behind is another of the true parts of Norwegian Ninja‘s “true story.” Created jointly by the CIA and whatever other shady ops groups were working for NATO at the time, Stay Behind was meant to be an already-in-place resistance movement should the Soviets move in and take over a particular country. As is often the case with shadowy organizations invested with a somewhat vague mission that causes members to presume they are above the law, some of the Stay Behind enclaves decided to get a little bit more creative with their anti-Soviet operations and started carrying out terrorist attacks meant to look like they’d been perpetrated by the Reds. In 1978, Norwegian police raided the home of Hans Otto Meyer, believed to be the head of a Norwegian Stay Behind group, and found a large cache of weapons and lord knows what else. Director Thomas Malling decided that the Meyer case and the Treholt case went together as well as bacon and syrup (don’t pretend like you haven’t done it), and the resulting tale is Norwegian Ninja. Think of it as historical fiction for the Cold War era.

Norwegian Ninja plays it pretty dry with the humor, though there’s more than a few overt jokes. Arne entering rooms by simply appearing (sometimes somewhat awkwardly) in a classic puff of smoke is delightful every time it happens. The ninja island is protected by a feng shui field that is modulated by turning foo dog statues slightly askew. The comedy is mixed in with a good dose of old school espionage action–the night-time raid on an oil drilling platform being the action highlight—and intentionally awkward (and thus somewhat more realistic) martial arts training and fight scenes.

But what really made the film special is its attention to the philosophy and spirituality behind what Arne’s task force is doing, in regards to both the martial arts and politics. During the opening mock recruitment video, Arne explains that the original ninja were not mighty warriors and assassins; they were farmers who understood the land and used their knowledge of local surroundings to stand up to aggressive, better funded, better equipped samurai looking to exploit the rural folk. Hell, it’s a more accurate explanation than we ever got during the ninja craze of the 1980s. Arne’s troop comes off like a force of well-trained hippies, complete with shaggy hair, Zen enlightenment, and campfire sing-alongs (which irritates the shaved-head, militaristic Otto to no end).

Similarly, the movie’s take on patriotism is progressive, especially as we operate now in a climate of hyper-jingoism and xenophobia. There’s a melancholy about Arne and his ninja, as it increasingly looks like their policy of understanding, of reasoning out a situation rather than simply charging in full of violent rage becomes antiquated and suspect. When action is called for, they act, but the ninja don’t like being dicked around by a self-serving bureaucracy or war-mongering hawks. That sort of carefully considered thought, that questioning of official claims and authority figures blustering and throwing their weight around, should be the norm, not the fringe. It should be the patriotic duty of everyone to keep a wary eye on our elected leaders and not accept their word at face value. Instead, we exist in an environment where even tepid questioning of authority is often met with shouting, madness, and cries of being unpatriotic.

One of the things I like about watching movies from other countries, especially movies that deal with the Cold War, is the different perspective and attitude one gets on the situation. I was in high school during the 1980s and remember the last throes of Cold War paranoia well, as well as the ways in which we in the United States dealt with it in popular culture (“Wolverines!!!“). Since I was also a rowdy punk in the ’80s, I was less likely to buy into Reagan era hate and doom scenarios than others, but I won’t pretend like the specter of nuclear war didn’t loom heavily over pretty much everything.My friends and I even had a nuclear war survival shelter built in the woods not too far from where we lived—and thank god the war never came, because had we been forced to rely on that shelter…!

Malling’s film places Norway and its central character of Arne where Norway actually sat: stuck between two grumpus super powers locked in a deadly battle of “made ya flinch!” Norwegian Ninja is not entirely anti-American (after all, the “American black ops organization goes rogue” scenario is plenty common in American films as well), just as it’s not entirely pro-Communist. What you have instead is the real/pretend Arne Treholt, a man who recognizes that the democratic side is capable of dictatorship-esque atrocities just as the Communist side is composed of actual human beings who aren’t altogether different than people on the western side of the Iron Curtain. What he wants more than anything is for these two bruisers to stop bullying smaller countries. And he wants to oppose corrupt militarists and politicians who use fear to manipulate populations and enrich themselves.

It’s an interesting political razor’s edge to walk, and a stance with which I am generally sympathetic. Being a proponent as I am of free speech and political expression, there’s little in the old Soviet style government that I find worth praising. At the same time, it breaks my heart to watch the self-proclaimed bastions of freedom slide further and further down the slippery slope to tyranny while hyping up an assortment of threats to “our way of life” in hopes of whipping people up into a paranoid hysteria that makes politicians more powerful, erodes civil liberties, and marginalizes reason. These sorts of things don’t happen in one big chunk. You don’t wake up one day and find yourself living in East Germany. Instead, rights are whittled away in little bits which, taken one at a time, seem acceptable, even prudent, until you begin to look at the sum of what’s been done. The United States isn’t a tyranny. But not being a tyranny doesn’t mean we aren’t being led in that direction.

Although Norwegian Ninja is spoofing the look of old espionage films, no one plays it goofy. There’s an earnestness in the performances that helps sell the central concept. As is almost always the case, playing it straight makes the comedy funnier than if the movie had been full of over the top cartoonishness and mugging. Norwegian Ninja is occasionally laugh-out loud funny, but for the most part, it strives for and achieves a more subdued sense of consistent amusement.

Familiarity with Cold War politics, Norwegian history, and of course, martial arts and espionage movies will augment your enjoyment, but I don’t see them as being necessary to find the movie entertaining. Norwegian Ninja puts its heart into creating its own believable universe and succeeds no matter how fantastic the events become. By the time they’re done building their little world, you discover that you’re totally invested emotionally in it and the bizarre, hippie-ninja-super soldiers who inhabit it. When Otto and his forces lay siege to the ninjas’ island with assault teams and carpet bombing, it’s downright upsetting—especially when one of the ninjas is bravely shouting, “We must save the animals!”

Aside from looking freakishly similar to the real Arne Treholt, Mads Ousdal plays the role with conviction. The supporting cast is similarly serious about absurdist material, and although the character of Otto is one that could easily lend itself to hamming it up, Jon Oigarden knows just how far to take it without taking it too far. The other character to get substantial screen time is rookie ninja Humla (played by Norwegian rocker Amund Maarud), who is very committed to the ninja force while also being totally confused by almost everything that goes on around him. Despite Humla’s mediocre performance during training, Arne ensures the youth that he will one day be the master of the ninja force. Exactly what this means, however, only becomes clear once Arne is targeted for elimination by Otto’s nefarious group of mercenaries. The rest of the ninjas are more thinly sketched, though they get enough development to make you actually care about what happens to them.

Author turned director Thomas Cappelen Malling opts for a largely documentary style approach to the narrative and camera work, though unlike many other faux-documentaries, he doesn’t over-indulge in shaking cameras and other irritants. Malling and cinematographer Trond Hoines don’t let the fake documentary approach serve as an excuse for shoddy filmmaking. I wonder sometimes if a lot of the people who go for the faux documentary look have ever seen a documentary. I mean, documentarians do still work really hard at things like cinematography, camera steadiness, and, you know, keeping the shot in focus and whatnot. Norwegian Ninja shoots for the polish of a documentary made by accomplished pros, and it nails it. As always, the dramatic scenery of Norway does its part to augment the cinematography.

What Arne Treholt (who died in 2023) actually did remains to be puzzled out. What he was thinking and how he felt when he did it are internal dialogues I can’t pretend to know. Upon his release from prison in 1992, he moved to Moscow and went into business with a former KGB general—though given his overall political philosophy, that’s not evidence of his guilt. His case was examined and re-examined, and the credibility of people on both sides of the fight often proved dubious. And in 2022, he spoke in support of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So, you know, not ideal. Whatever the case of the real Arne Treholt, it’s easy to sympathize with the ninja version of Arne Treholt and the precarious situation in which he and his scruffy band of elite soldiers find themselves. That’s not to say that the politics of Norwegian Ninja are front and center or especially heavy on the shoulders. This is an action-comedy after all, and while politics are at the heart of the events, persuading viewers of one political philosophy or another is not among the film’s top priorities—though encouraging people, even through fairly absurdist means, to question “the official story” probably is.

Norwegian Ninja is a rich enough storytelling experience that you can approach it as satire, as action-comedy, as a political thriller, as a philosophical treatise. It operates on multiple levels and has a lot to offer. Films like this remind me of why I love writing about film. You can chug along, even start to get jaded and think you’ve either seen it all, or at least seen all that’s worth seeing, and then, like a Scandinavian special forces ninja, up pops a movie like this that makes you grin and appreciate movies all over again.