I was promised “completely bonkers” and was not disappointed

Aalavandhan (aka Abhay, 2001) first came to my attention when I was flipping through the meager selection of Indian films for rent at a local underground video store. I was greeted by a cover featuring a screaming bald man, covered in tattoos and brandishing a huge knife, flying down the side of a skyscraper. At the top of the box, an employee of this particular video store had slapped on a label then scrawled a simple message in black Sharpie: “Completely Bonkers!!!” I was sold. In my world, there’s no greater critical endorsement than “completely bonkers” followed by three exclamation points. With considerable glee and a jaunty song in my heart, I trotted up to the counter, paid my rental fee, and rushed home giddy with anticipation.

I was not lied to. Aalavandhan is indeed completely bonkers. As I would later learn, it was also, at the time, the most expensive Indian film ever made, and it pioneered the use of digital effects in Indian cinema. It’s over-the-top nature set South Indian films on a wild course toward more and more insane, over-the-top action, culminating in eye-popping action extravaganzas like Bahubali and RRR. It was also wildly controversial, reveling in violence, insanity, sex, and drug use—none of which are exactly rarities in big-budget Indian cinema but were (and still are) not usually present in such quantity as Aalavandhan.

A note about the following review: Aalavandhan was originally filmed in the Tamil language. Concurrently, a version in Hindi was filmed as well, and it was also dubbed into Telugu (India is a big country with a lot of different cultures and languages). Both of these latter versions were titled Abhay and were the version I saw first. One of the characters was also renamed Abhay (from Nandu). So forgive me below if I absent-mindedly switch between the two.

Iconoclastic Tamil actor Kamal Hassan stars as heroic moustachio’d Vijay, leader of a crack team of anti-terrorism commandos. Vijay is about to marry newscaster Tejaswini (Raveena Tandon). On this joyous occasion, Vijay decided he should visit his psychotic brother, Nandu (Abhay in the Telugu and Hindi versions) in the mental asylum and tell him the good news. I’m not sure what sort of reaction Vijay was expecting from the gibbering, bald nutcase (also played by Kamal Hassan, thanks to head-shaving magic) who murdered their stepmother when he was twelve years old, but Abhay doesn’t take the news too well. He proclaims Tejaswini to be a man-eating succubus who must have her throat slit in order to save Vijay. All things considered, Vijay decides against inviting Abhay to the wedding, obviously afraid of what sort of Best Man speech the guy would make.

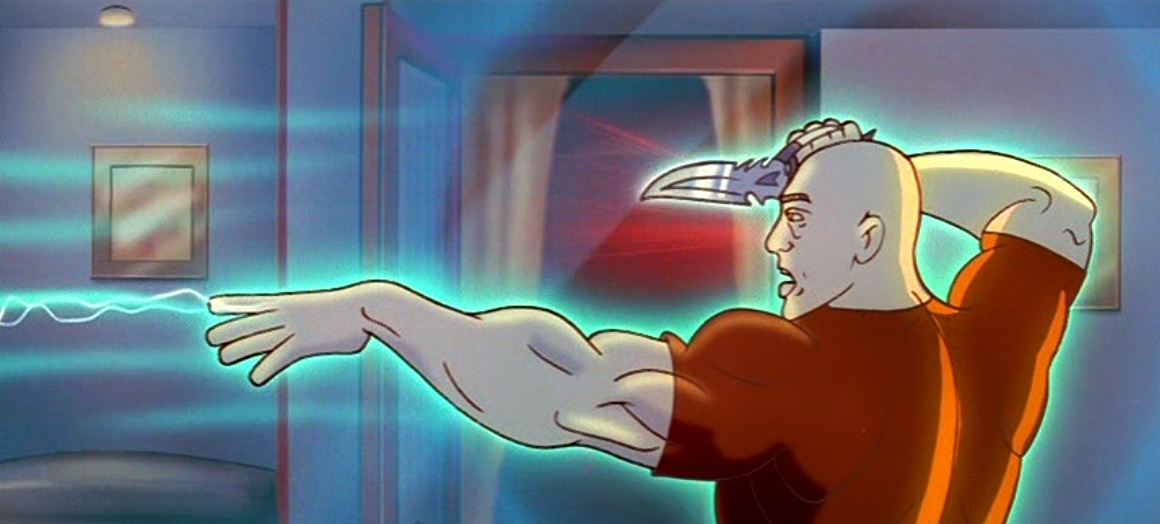

Nandu is now obsessed though, and he soon orchestrates his escape from the asylum and begins a completely bizarre and violent quest to track down and murder Tejaswini. Much of the film revolves around Nandu’s quest, much of which occurs under the influence of drugs. This includes philosophical congress with a giant Ronald McDonald, a trip to a wild stage show, frequent beratement by the disembodied head of his stepmother, obsession with sleazy pop star Sharmilee (a cameo by Dil Se‘s Manisha Koirala), and even an extended segment in which his world becomes a cartoon.

He also makes time to call and threaten Vijay and Teju to make sure they know he’s coming to murder her. All in all, it’s a lot for the newlyweds to deal with, especially when they discover the abuse Nandu endured as a child. Still, however much Vijay may love his brother, and however sympathetic he may be for the sacrifices Nandu made when they were children, when the maniac shows up newly tattooed and brandishing big-ass knives, Vijay calls upon his special forces training to protect his family.

Director Suresh Krishna and writer/star Kamal Hassan set lofty goals for themselves. Aalavandhan was to concentrate heavily on the world as perceived through the eyes of its titular drug-addled psychopath, which meant ample opportunities to ratchet up the weirdness. To realize Nandu’s hallucinations and insanity, as well as facilitating Hassan playing dual roles without relying on age-old split-screen trickery that can give us so many Amitabh Bachchans in a single film, they tapped the visual effects wizardry of Das Chinmay, Sylvan Dieckmann, and George Merkert, who between them have logged major special effects work on big-budget Hollywood films like Serenity, Superman Returns, Poseidon, Starship Troopers, and Total Recall. Regardless of what you may think of those movies, there’s no denying that Hassan and Krishna were calling in some visual effects big guns. He also enlisted the consulting talents of veteran Australian stunt choreographer Grant Page, who cut his teeth in the wild world of Aussie action cinema, including Mad Max (not It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, as was once reported and thus oft repeated).

A huge amount of hype surrounded the film and the many special effects it would boast. Kamal Hassan was a wildly popular star who, even in his later years, commanded substantial box office. He also had a rep for taking big risks with his material, and Aalavandhan had been on his mind since the 1980s. Expectations were sky-high, and Aalavandhan was poised to be the biggest release of 2001. Alas, to be a big release, people have to actually show up for your release.

Instead, and for a variety of reasons at which analysts can only guess, audiences shied away from the film, and it wasn’t long before the biggest film in Indian history became one of the biggest flops in Indian history—like Megaforce, except that the effects are better even when they’re bad. The ballooning budget and production delays caused some people to lose interest before the film was even finished. Others stayed away because of the controversial adult content. In the end, Hassan and Aalavandhan were just a little too far ahead of their time, though time would eventually discover and embrace the film.

Still, box office failure and critical and audience puzzlement at just what the hell Hassan was trying to do doesn’t mean the film isn’t spectacular, especially from the viewpoint of a cult film fan. It packs in a ton of breakneck action, some quality acting, and some absolutely inspired freak-out scenes. It’s absolute delirium, and for the most part the film manages to keep the frantic pace. Only once, during a lengthy flashback detailing the events that lead up to Abhay murdering their mother-in-law, does the film stumble. The flashback is essential but far too drawn-out. The highlight of the overlong flashback scene is a prancing, dancing half-naked village idiot who keeps you thinking that the film is going to delve into weird pedophile territory, though it never does. The guy is just a harmless weirdo. Hassan could have chopped this sequence in half and had a stronger film. As it is, it serves as a bit of interesting back story in a sequence that gets tedious, but at least it recovers for a blowout of a finale.

The special effects quality varies wildly, which makes sense given that 1) they were aiming for far more than could be delivered in 2001, and they were figuring it out as they went. But you can’t say they weren’t all in on the concept. The film revels in visual flash. Even when it over-indulges, it’s still pretty fun. The bulk of the effects are up to the standards of Hollywood productions of the time (2001), and they set a new benchmark for the quality of effects work in Indian films. The animated sequences are also a real treat. The martial arts choreography isn’t spectacular, but it’s still pretty good. There are some stand-out action sequences, including a car chase that sees Nandu leaping from vehicle to vehicle (which reportedly took 15 days and 39 cars to film) and the final showdown between the two brothers, that make Aalavandhan a stand-out action film as well as a screwed-up acid trip of a movie.

Kamal Hassan is great in his dual role, creating two characters so individualistic and unique that you never even realize you’re watching the same actor in dual roles. Vijay is stable, caring, but determined to protect his bride from his brother. Nandu is a scenery-chewing (literally, at one point) madman with a tendency to turn into a cartoon. Raveena has little to do other than be occasionally stalked and menaced by Nandu while she looks pretty, but one of my favorite actresses, Manisha Koirala, is hilarious as a sleazy cokehead pop star who tries to bed Nandu before ending up on the bad end of one of his drug-induced hallucinations. She appears in a weird musical number, then shows up for a hotel scene, which she plays out almost entirely in English for whatever reason. Kitu Gidwani appears in flashbacks as the manipulative mother-in-law, while Anuradha Hasan plays the saintly real mother of Abhay and Vijay, who appears frequently to Abhay as a sort of ghostly Ben Kenobi.

Even at three hours, Aalavandhan skips breezily from one crazy moment to the next. Hassan has a reputation as one of India’s bolder and more unconventional risk-takers, and Aalavandhan was certainly a risky movie. It’s equal parts psychological horror, Hong Kong action film, fantasy effects film, and musical comedy. Even Indian audiences accustomed to seeing every genre imaginable crammed into a single film didn’t really know what to make of Aalavandhan‘s gloriously madcap combination of ingredients. Although it was a financial failure, as a piece of mind-blowing phantasmagorical entertainment, you’d be hard-pressed to find a film more enthusiastic.