Though I didn’t realize it at the time, Teleport City was created for one reason and one reason only: to eventually review Intrepidos Punks. In fact, it wouldn’t be entirely beyond the pale to say that my entire life has been leading up to the moment I first heard of, then tracked down and watched this overwhelmingly fantastic slice of punk rock exploitation from, of all places, Mexico. At its heart, Intrepidos Punks is really nothing more than a by-the-numbers biker film updated for the looser censorship morals of the 1970s. But the frosting it layers onto the biker film cake make it into something utterly sublime. Everything I’ve ever been interested in — exploitation films, sleaze, punk rock, luchadores, scantily clad new wave girls, dune buggies — it all comes together in this perfect storm of day-glo mohawks and ten foot tall teased-hair brilliance.

To fully grasp exactly how much and why I love Intrepidos Punks requires a rather long-winded tale of a young lad growing up in semi-rural Kentucky. Or rather, it doesn’t require that at all, but I’m going to do it anyway.

Toward the end of eighth grade, I found myself increasingly discontent with what had once kept me happy. Polo shirts, Morris Day and the Time, and “Sussudio” just didn’t do it for me anymore. Things that had once satisfied my pubescent desire for entertainment were increasingly hollow and unaffecting. Roller skating parties, “Oh Shiela,” school dances. Everything was losing its luster (though I have since made my peace with Ready for the World, though to this day, I maintain that “Sussudio” can go to hell). Gnawing at the back of my mind was a feeling of dissatisfaction with what was offered to me on a daily basis. The feeling was becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. And more than that, I found I didn’t want to ignore it. Everyday, the feeling that I was not a part of what was going on around me grew.

It could be dismissed simply as “those raging hormones,” a by-product of that tumultuous time in our lives when our voices change and we start to grow hair on parts of the body where there didn’t used to be any hair, like on the bottoms of our feet and on our tongue. But it seemed like something more, something that couldn’t be idly dismissed as adolescence. Certainly I was going through my formative stage, and I am painfully aware of all the stupid things I did and felt as a budding teenager. This wasn’t one of those things though. After all, everyone else was going through the same biological hurricane. This was definitely something else. I started listening to more metal, simply because it was considered disrespectful and taboo. But even that rarely hit a chord with me. I started listening to more classical and jazz, simply because I didn’t know what else to do, but I didn’t really like those, either. They were the only alternatives I could find since the nearest city was Louisville, which might well have been a million miles away for an eighth grader with nothing to his name but a K-Mart dirt bike.

Spawned by a controversy during a school talent show, in April of 1986 my class was seized by an Outsiders-esque schism between the social castes. The teachers in charge of the talent show had decided to celebrate a Cyndi Lauper lip synch act by a group of preppie girls while, at the same time, scoffing at the heartfelt though off-key rendition of “Sister Christian” by a group of budding young metalheads. Thus was born the great battle between the rich kids and the poor kids, or as it was back then, the “preps” and the “scums.” At some point, I realized that I had no side in this. This was a fight between two groups to which I did not belong. I empathized with the scums but I wasn’t one of them. I knew and liked a lot of the preps, but I wasn’t one of them either.

That summer, cable television finally came to our area. Up until then, if I wanted alternatives to networks that signed off at midnight, I had to spend the night out at my friend Robby’s house. They had a satellite dish, and multitudinous were the nights we would feign sleep in order to turn on the television and get a night’s worth of softcore porn starring Sylvia Kristel. When cable finally graced our domicile, it was something less than spectacular. I don’t know what I had been thinking. Like my parents were going to get the Playboy Channel and HBO just so I could stay up all night watching Sylvia Kristel and R-rated barbarian movies featuring naked sorceresses. We had no premium channels, and what I found on the other channels was simply a repeat of the crap on network television. Like I needed WOR to see Perfect Strangers.

The only thing on cable that caught my eye was a show called Night Flight that aired on the USA Network. Night Flight featured all kinds of crazy shit I couldn’t believe. SubGenius videos. Dynaman episodes. Experimental short films. That Fantastic Planet cartoon movie a million fucking times. Residents videos that both baffled and enthralled me. And punk rock. I sat wide-eyed in the basement as I watched footage of the Bad Brains, Cro Mags, Dead Kennedys, and Minor Threat. I watched interviews with bands who decried the rule of the rich, the religious right, and conformity. I watched Jello Biafra croak, “It’s a conspiracy!” I watched people skateboarding, slam dancing, expressing themselves, and having fun.

“Holy Shit,” I thought to myself.” This is it. This is what I’ve been looking for.” It was a subculture that was loud and rebellious, that was totally unlike anything I’d ever been exposed to, that offered me the alternative for which I’d been searching so desperately. It was an option I never knew I had. Trapped in the wilderness of Buckner, Kentucky, I finally stumbled across a radio transmission from the world for which I’d been searching. I was giddy as a SETI scientist picking up a transmission of “Satisfaction” coming from Alpha Centauri. It was my first glimpse at a larger world, at something I’d been looking for but couldn’t describe to anyone.

One night, Night Flight ran a documentary called Another State of Mind about a tour involving Youth Brigade and Social Distortion (with special appearances by Minor Threat). It was my first real exposure to the philosophy behind punk rock, or at least behind the school of punk rock with which I would come to identify. It was a look at how kids all over the place were eschewing mainstream society, were setting up their own shows, their own bands, printing their own zines and records. To this day, I have very vivid memories of the words spoken by Shawn Stern and Ian MacKaye, both of whom were interviewed extensively in the film.

I had no avenue for getting hold of records. Night Flight planted the seed but didn’t furnish addresses for germination. And the likelihood of walking into the local IGA and finding a copy of Out of Step was slim. No joke — the Crestwood IGA put Chef Boyardee in the “foreign foods” section. It was still several months away from me finding my first copies of Maximumrocknroll and Thrasher, featuring ample ads for JFA and Septic Death and the key to mail-ordering records that would then take like eight weeks to ship to you. The best I could do at the time was to make tapes of the television, recording Shawn’s interviews and the many songs (even fractured versions) by Social Distortion, Youth Brigade, and Minor Threat, as well as the other videos and snippets that aired on Night Flight. As the credits rolled, the Social Distortion song “Another State of Mind” began. There are moments in life that are such amazing functions of coincidence, timing, serendipity — call it what you will. Rarely has a song been so perfectly timed with a particular moment in my emotional growth. More than anything else in the world, I needed to hear that particular song at that particular time. It may sound drastic to say “Another State of Mind” changed my life, but it did.

As a newly minted punk rocker, I was of course an insufferable prick about punk rock. Judgmental and humorless, sneering at anything I interpreted as a misguided and inaccurate depiction of punks in cinema and television, of which there were ample examples in the 1980s. And of course, everything was wrong unless it was my definition of what punk rock was supposed to be. Of course, as one gets older, one often grows to appreciate on some humorous level not just one’s own well-meaning but ridiculous rage, but also the hilarity of how one’s subculture was depicted by people who had no part in it. Which means that these days, the rampaging monstrosities that passed for punks on film in the 80s and 90s are a source of endless amusement for me, and movies in which they terrorize the norms make up a larger and larger portion of my film collection every year.

And when it comes to punksploitation movies, you’re going to be hard-pressed to top Intrepidos Punks. Even genre heavyweights like Class of 1984 and Never Too Young to Die pale in comparison to this batshit insane paen to everything that was glorious about cinema’s misrepresentation of punks. It’s basically every alarmist rumor about punk rock — not to mention just about every single convention of 70s exploitation film — rolled into a single representation: drugs, orgies, spitting, bad hair, Satanic rituals, murder, rape, loud music, makin’ faces at the squares, and with the addition of dune buggies and, for some reason that can only be “because it’s Mexico,” a luchadore. We begin with a line of nuns walking down the street to a bank, which they promptly rob. Because these aren’t nuns at all; these are the women of the titular intrepidos punks, amassing cash so they can buy weapons and drugs that will help them free the imprisoned male members of the gang.

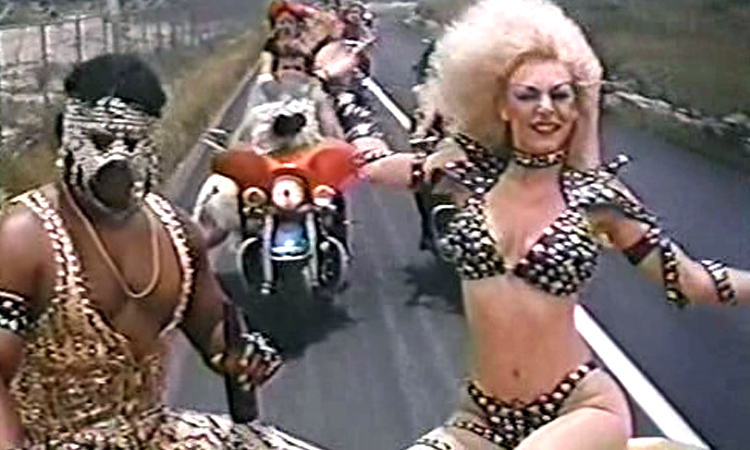

The reveal of the female punks is perhaps the greatest transformation scene in cinema history, as they strip away their nun duds to reveal leather thongs, metal bikini tops, sequins, chains, lace, mesh, breasts, and all manner of candy colored punk rock hair. The leader is the sneering, snarling Beast, played by actress Princess Lea (obviously her real name), and the height of her platinum blonde hairdo defies all known physics. And though her hair and studded leather bikini may be one of the star attractions, my heart was immediately stolen by the girl with the choppy red hair and spider-web face paint. For me, the true stars of the film are the girl with the spiky red hair and spiderweb face paint and the guy with the bright red poodle perm mullet, Fu Manchu mustache, lazy sort of expression, and exceptionally proud posture.

In what seems to me an overly convoluted scheme, the girls’ plot to free their men from prison by kidnapping the wives of the prison officials. Unfortunately, when Beast makes her ransom call, the warden and his guards are too busy having an orgy to pick up the phone. This drives the lion-maned femme fatale into a rage in which she gives some of the other male punks permission to rape the wives, which leads to one of cinema’s more bizarre scenes of tasteless rape. The men sort of just howl and rip and clothing and giggle while rolling around on top of the screaming women — all while the intrepidos punks’ apparent house band sets up in the living room and plays a set. Sadly, even this doesn’t stir the cops to action, so Beast is left with no alternative but to chop off one of the wives’ hands and mail it to the prison.

With that business taken care of, the punks are freed from prison, and the rest of the gang arrives to pick them up in their sweet dune buggies and trikes — none of which is opposed in any way by any cop, despite it being something of a high profile arrival. Among the punks freed from prison is gang leader and Beast’s main squeeze, Tarzan, played by beefy luchadore El Fantasma and wearing outfits that are just slightly more flamboyant than those sported by Grace Jones in Vamp and Tamara Dobson in Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold. With the gang now back to full strength, they are free to do what roving gangs of punk bikers and dune buggy aficionados do best: tear around the desert, set people on fire at gas stations, and retire to their cave lair to have black magic modern dances and orgies while playing loud music.

Meanwhile, we are occasionally forced to endure scenes of the film’s ostensible heroes: two mustachioed redneck cops who seem really crappy at their job but are supposed to be some sort of super fuzz. Eventually, they get around to chasing after the punks, but mostly, they sit around in bars and leer at women while talking about trying to get laid. Ironically, these greasy heroes seem far sleazier than the murderous, rape-mad villains of the movie. The punks, while partaking in more vile acts per minute than can be processed by even our most powerful super computers, are portrayed in my opinion not as actual evildoers but are instead like a pack of wild animals — complete with the fact that they communicate mostly by hooting and growling. They are feral creatures who, rather than being immoral, are simply amoral in the way a wild jungle beast is amoral. The cops, on the other hand, are just a couple of scummy douchebags.

The first thing you might think when you hear a summary of Intrepidos Punks is that it’s drawing substantial influence from the Australian post-apocalyptic action classic Road Warrior, only then the Mexicans decided that every single character should be pink-mohawked feral madman Wez, and also Wez shouldn’t play it so subtle. But Intrepidos Punks was made in 1980, a year before Road Warrior hit screens and inspired a decade of Italian and Filipino imitations. And while I wouldn’t doubt that Mad Max, the precursor to Road Warrior, bore some responsibility for inspiring Intrepidos Punks, the fact is that Mad Max is an altogether less flamboyant and psychotic take on the biker film, populated mostly by bikers who just look like bikers. Which means Intrepidos Punks thought of its candy-colored villainous punk gang more or less all on its own.

Whenever the punks are on screen, this movie is a tour de force of everything that is offensive and wonderful about exploitation films. They are a force of nature, the nihilistic attitude of Sid Vicious amped up on god only knows what substance, but with a twisted sort of innocence about even the most heinous of crimes. They are not rebelling against the standards of society so much as they are entirely unaware that any sort of standards exist. And since none of the punks has any background or character beyond the color of their hair, their destructive behavior lacks the sort of gritty, “horrible childhood” upbringing that might infuse it with any sort of purpose. They merely are. They sprung fully formed and wrapped in lace and leather from the fabric of the universe, the most illogical extreme of the Id.

Like I said, beneath the surface, this is basically a classic old biker film: the gang rolls into town, drinks and parties, terrorizes the locals, then gets busted by the cops. And sadly, like classic biker films, the profound greatness of its great moments is tempered by the moments that will have you eyeing the fast forward button. Whenever the film shifts to the story of the cops, the film grinds to an annoying, tedious halt. Nothing’s worse than spending time with two dull cops in jean jackets taking about law enforcement when you know somewhere out in the desert a sparkly luchadore and his big-breasted gun moll are presiding over gladiator sex games and wheelie competitions while Satan’s baby doll gyrates around the campfire. Yes, please leave that for long scenes of two middle aged squares sitting in a restaurant talking about how they wish they could get laid more often.

Every second you spend in the company of the cops pushes you closer to the extreme occupied by the punks — sort of like rooting for the killer in a slasher movie. Luckily, every time the movie pushes you to the limits of your patience with the cops, it rewards you with more scenes of naked cavorting punk-beasts jumping sand dunes and swapping sex partners, or shooting up the place just for the hell of it. Although this movie may not get much right about the reality of punk rock, it certainly captures, even if only accidentally, the anarchic spirit that birthed the movement. And luckily, this movie features an oddly tempered finale. I mean, don’t get me wrong — it’s a pretty insane explosion of cops and post-apocalyptic punk rockers shooting at each other, but a number of the key punks don’t get blown away; they merely get arrested, leaving the end of the film open for — well, I wouldn’t call it an inevitable sequel, but a sequel there was, never the less.

There’s not much I can say about the cast, mostly because I don’t know who is who other than the very obvious duo of Tarzan and Beast, and even then I know little more than names. The only Mexican wrestler I know of by the name of El Fantasma is a more recent entry to the ring and dresses like the pulp comic hero The Phantom. If the Fantasma of this movie had an actual in-ring career, I can’t find anything about it. In Intrepidos Punks, he makes for an impressive looking physical presence, but as a character, well, he’s more of a well decorated prop with a mask that looks like it was made out of an old chandelier. Ostensibly, he’s the leader of the punks, but it’s pretty obvious that the real power in the gang exists beneath that towering mound of teased blonde hair perched atop the head of Beast.

As Beast, Princess Lea commands the screen every time she steps onto it. Unfortunately, her chosen stage name makes finding any information about her as difficult as it is for El Fantasma. She appeared in a fair number of movies, and judging from what scant info is available on each of them, she probably spent most of her screen time dressed once again in tiny black bikinis. I’d like to track some of them down, because she rules Intrepidos Punks with an iron fist. Even in a movie as packed with over-the-top punk/new wave style on acid, Princess Lea’s Beast stands out as a force all her own. She makes a decent counter-balance to the hulking but relatively bland Tarzan. Together, the two of them remind a little of Diabolik and his girlfriend in Danger! Diabolik. They exist in a world completely divorced from any mainstream concept of morality, yet the two of them seem very much in love in their own animalistic way.

The rest of the cast of punks seems to be trying their damndest to keep pace with their costumes. Never mind that most of the men seem to be middle aged in a year before we were having to deal with middle aged punks. Each of the actors throws themselves with abandon into their roles with the same enthusiasm the costumer designer threw into dreaming up outfits of which even Malcom McClaren would have been envious. There is plenty of authentic punk regalia on display, as well as a heap of new wave, biker, and glam metal in a year before…eh, I don’t really know when glam metal came into being as a style, but I figure Intrepidos Punks must have been at the very forefront of that fashion trend as well. Who knew the entirety of humanity’s future was predicted by the costume designer for Intrepidos Punks? The punks and their regalia are more than enough to propel the movie through the murk of the boring cop scenes.

Intrepidos Punks should be seen by pretty much everyone who ever called themselves punk, as well as by anyone who appreciates trashy, sleazy exploitation films. It’s absolutely mad, meandering, goofy entertainment. Despite the slow spots whenever we are supposed to be learning to appreciate the cops, this movie otherwise blazes forth with directionless glee, leaving nothing but scorched earth and empty packets of Manic Panic hair dye behind it. Whoever came up with the look of the punks deserves to be enshrined in some sort of hall of fame, and possibly in every hall of fame. Released in 1980, the crazed biker punks of Intrepidos Punks not only predate the archetypal post-apocalypse punks of Road Warrior, but exist as one of the earliest examples of punksploitation in a feature film. Intrepidos Punks is a colossal juggernaut, a true giant striding across the landscape of sleazy movies. If you have not seen it, you will notice there’s probably a little hole in your soul. A hole shaped exactly like a busty blonde in a chainmail bikini, sporting gigantic hair and a grenade launcher. Let Intrepidos Punks plug that hole and finally make you complete.

Release Year: 1980 | Country: Mexico | Starring: Rosita Bouchot, Martha Elena Cervantes, El Fantasma, Juan Gallardo, Alfredo Gutierrez, Princesa Lea, Ana Luisa Peluffo, Olga Rios, Juan Valentin, Armando Duarte, Luis Alcaraz, Martin Urieta, Octavio Acosta, Antonio Zuniga, Fidel Abrego, Alejandra Beffer, Bianca Nieves, Viviana Olivia, Rosalinda Espana | Screenplay: Beto Marraquin | Director: Francisco Guerrero | Cinematography: Alfredo Uribe, Jr. | Music: Three Souls in My Mind